By Dr Sue Sheppard, Educational Psychologist and Module Leader for Real Training’s postgraduate courses in autism. This article originally appeared in Teaching Times.

If you could model a learning environment that was intended to be an assault on the senses it might very much look like a typical school.

To a neurotypical person this might be difficult to comprehend – yet for a young autistic person, our schools can be the epitome of chaos. Hundreds of children shouting noisily, teachers raising their voices to be heard, bells going off, the constant echo of footsteps in corridors, people talking all at once in lessons, dense slides, bright lights, itchy uniforms, a bombardment of smells in the dining room.

It can take a lot of energy just to be there.

For autistic girls, however, this exhaustion is often multiplied due to their need for perfectionism and the pressures of masking as they strive to meet social expectations. The more we learn about their routines, including ruminating, the clearer it becomes that this can be at the detriment to positive wellbeing. Autistic girls have even been described as ‘little psychologists’ by some in the field, due to their tendency to over-analyse events and experiences.

Gender stereotypes have shifted over the last ten years or so and we now recognise the nuances of autism in girls. I’ve spent thirty years as an educational psychologist, developing a specialism in autism and in recent years have increasingly worked with young autistic girls. Many of these girls report feeling isolated, misunderstood, anxious and exhausted. There is a significant increase in those who find attendance challenging and many have been out of school for extended periods of time. These students may gain other labels, for example, anxiety or depression which become the focus and their wider needs can then be ignored. It has been suggested that up to 80% of autistic girls remain undiagnosed at the age of 18.

Much of what I have learned comes from listening carefully to autistic girls and women and their families. Here’s what I would advise teachers and leaders to focus on;

Provide meaningful ways to connect

Research is showing that a ‘sense of belonging is key’ for autistic girls who need to find a feeling of community just as much as their peers. Many autistic girls can struggle with this at school, however, some girls might be very sociable and talkative and others will be more shy and isolated. It is important to ensure autistic girls spend regular time with named key staff who can really get to know them and ‘empower’ them to share their views around what works well for them and what makes challenges worse.

In a recent video produced by the Donaldson Trust, Erin Davidson, a 17-year-old with autism explains that “the feeling of isolation at school was, well, crushing because I could be surrounded by people and still be entirely alone.”

Schools can help by setting up supportive lunchtime or drop-in groups for neurodiverse girls so they find peers they can relate to and perhaps even gain support from. Providing peer mentorship schemes or buddy schemes with empathetic neurotypical peers or trained wellbeing ambassadors can also be considered, with guidance from teachers or support staff.

Breaktimes can be problematic because they are unstructured. Providing activities where autistic girls can bond with a small group in shared activities such as art/craft, origami workshops, digital animation or film clubs, reduces the need for scripted small talk and allows them to talk about an interest with others who are equally passionate. It might bring added benefit of providing some much-needed sensory stimulation or opportunities for relaxation.

Recognising anxiety triggers and managing transitions

Emerging research suggests autistic girls may be more prone to anxiety than autistic boys. Before adaptations can be made, we need to identify the triggers for each individual. Often, for girls, this can be related to unexpected changes, a lack of control over transitions and a need for perfectionism.

Classroom-based solutions might include; pre-warning of changes, sticking to ‘set’ seating patterns and allowing autistic individuals to leave the classroom five minutes earlier than their peers when it is quieter. At the same time, it is very important to ensure they do not find themselves ‘standing out’ even more. They may need more individual instructions to get started and visual supports and prompts, plus reassurance that they are on track.

Outside of the classroom, anxiety drop-in workshops can help equip girls with calming strategies, breathing techniques and ways to understand and avoid catastrophizing and negative thought patterns. One technique I often find works well in individual work is the ‘size of the problem’ method of viewing their concerns. Introducing the idea of a ‘stress bucket’ has also been effective as has teaching about ‘automatic negative thought patterns’ and using ‘laddering and rating scales’.

Visual demonstrations of ideas are important and analogies often seem to help. Additional support from staff who have specialist skills and autism training will help each girl build up a personal ‘toolkit’ of strategies to understand and manage anxiety. It takes time, but is very important, as is the encouragement to trial ideas.

Reducing sensory overload in the classroom

Reducing sensory overload in the classroom; it is important to recognise that individual needs will be quite different here, so teachers should work closely with the young person to identify what helps, whether that’s allowing her to wear noise-cancelling headphones or providing a preferred seat at the front of the class or pulling down blinds etc. Some schools also provide the opportunity to use screens at workstations or a quiet zone. Individuals will differ and may experience hyper and hypo sensitivity to sensory input. I usually carry out sensory audits as part of my assessments. Take note, as well, that the dining hall can be hugely problematic and separate spaces for eating lunch may be needed.

Some girls will find the concept of pair work uncomfortable, others end up leaning on just one solitary friend. Teachers could steadily build up a small rotation of ‘trusted and preferred’ peers to increase the quality of social interaction and also help broaden the ideas that are discussed. Giving set roles in advance which draw on their strengths is useful, for example, appointing a girl who has skills in drawing as the illustrator.

If the pace of lessons is a challenge, providing opportunities for remote or virtual work, such as collaboration via Google documents and allowing ‘time to process’ thoughts can also be beneficial.

Teaching self-compassion

Girls who gain a diagnosis can feel more understood, but this journey can take time. Building positive affirmations into the routine of school life and teaching self-compassion can help guard against this. Perfectionism and over-analysing are common traits in autistic girls, so teachers should work with students to set realistic goals and teach that failure can be a benefit to learning.

Recognising and developing strengths; providing an outlet to work on and highlight strengths is essential. Take the lead from the individual and identify areas she enjoys e.g; drama, art, music, literature, baking, any sports, forest school skills, design and construction etc. Personally, I have seen girls who’ve been put in charge of social enterprise initiatives linked to their interests, such as catering for school events, really thriving in secondary school.

We should celebrate areas where they do excel e.g. specific subjects, strong memories for facts, and good vocabularies. Often autistic girls have rich imagination and creativity and are strong with logical systems.

Regular rest and restore opportunities

For the majority of autistic girls masking and/or sensory overload is exhausting and they need opportunities to ‘recharge’. This could be a time-out system from class, quiet zones for break times and access to a ‘safe-haven’. They need ways to access safe spaces in school where there are named adults they can turn to. Reduced timetables at GCSE level can also facilitate positive learning outcomes.

While, in my experience, later arrival times can sometimes add unnecessary pressure about being treated ‘differently’ and ‘standing out’, slightly earlier departure times and/or relaxing or solitary activities before it is time to leave school can, and should, be offered. This provides the young person with an opportunity to decompress, get away from the sensory overload of school and travel home at a quieter time of day.

Working very closely with parents

Autistic girls need opportunities to unmask. They may hold it together during the school day but then release frustration or anxieties when they get home. Having open lines of communication with parents is essential, often school professionals will think that a young pupil is coping fine, but parents will have a very different view. In her highly informative video about spotting the signs of autism, Immie Swain describes how she would “keep it together at school but then when I got home everything would go wrong.” Schools need to know this whole picture and listen to parents. Alleviating pressures at school can make life at home easier. Sleep issues are also common and will further impact learning if not identified and supported.

Specific PSHE advice

I don’t like referring to autistic people as vulnerable learners, because it’s often our artificially created “neurotypical” environment that renders them that way. Autistic girls may be very adept learners, however, they can struggle to be flexible in rapidly changing social situations. Their lack of natural ability to pick up on social cues can make them more likely to be vulnerable to exploitation and bullying and in some cases victims of sexual assault. Teaching them how to stay safe will be important.

Schools might consider getting special-trained staff to teach sex-ed to autistic girls who often don’t discover intimacy until much later or indeed prefer not to have physical intimacy. They may also need more support when it comes to things like self-care and diet. Eating disorders can be present and need specialist support but eating issues may also relate to sensory factors or routines relating to calorie counting and specific diets. Schools need to be mindful and seek advice when it’s required.

Alternative female role models; some autistic girls might initially try to copy the most popular girl in the school or influencer on social media, but usually end up finding their own style. Highlighting positive neurodiverse role models in lessons can help them broaden their idea of what it is to be successful. There is a greater likelihood that autistic girls will not conform to gender norms and they may have a more unique understanding of interpersonal relationships.

Access to animals and nature

Time spent with animals and in nature can help alleviate anxiety, as well as helping with social interaction. Autistic girls often love their pets and are drawn to animals and report finding them more predictable than people. Whereas boys with autism may be more fixated on mechanical things, girls tend to have special bonds relating to animals and build positive relationships in this way. Schools that have a ‘school dog’ or links with horse riding centres or local farms have utilised such programmes with success.

Using alternative sports as an outlet for confidence-building

Sport can be another way for autistic girls to tap into a community as well as generally releasing endorphins. If your pupil finds team sports challenging, then offering her engaging solo activities such as fitness suites, wall climbing, swimming, and trampolining might also serve a similar purpose. Athletics is often popular. Sometimes, the most compassionate thing to do is just to let her sit out some PE activities (especially team-based ones).

Final thoughts

Autism has been vastly under-diagnosed in women and many education professionals are only now just beginning to learn how to spot the signs in the current generation of young girls – some of whom go to incredible lengths to camouflage their ASD.

Although autistic girls may be sometimes be quiet and not seek the attention of the group, this does not always mean they are ok. As they go through school and ‘informal rules’ around female social lives become more complex, the effort required to blend in will become more intense. It can feel isolating and anxiety-provoking if you want to keep talking about horses or manga characters, but your peers have moved on to other things.

It is vital, therefore, that individual needs are clearly identified and the right one-to-one support is put in place. This means not just making adaptations for multi-sensory needs within the classroom, but considering wellbeing and self-confidence in a broader context that will promote a ‘sense of belonging’, as well as increasing confidence and happiness. Sarah Hendrix, an autism advocate, speaker and assessor, has created a great video exploring how to do this.

Some of this requires a shift in mindset. Rather than simply trying to coach girls about how to fit in and improve their social skills – we should also be enabling them to find those moments of meaningful connection where they can genuinely be themselves. We also need to listen with care to identify solutions to any presenting challenges and we will need to be creative and highly flexible.

In a recent survey, only 14% of secondary teachers said they received more than half a day’s training on autism. Given the nuances of how ASD presents, particularly in girls, it is difficult to see how this can be sufficient. We need a whole school approach to build an autism-friendly school with good levels of training for all staff and an ‘autism champion’ who takes the lead.

Auditing autism provision in your setting should be a priority, both to celebrate what you are doing well, but also to identify an action plan for enhancing provision for this group.

Dr Sue Sheppard is a practicing educational psychologist. She is also Real Group’s specialist EP for autism and module leader for Real Training’s postgraduate courses in autism. She has been a consultant to the Lorna Wing Centre for Autism (part of the National Autistic Society) since 1996 and is embedded in the internationally recognised DISCO diagnostic training team.

After starting her early career as a specialist teacher, Sue worked as an EP for numerous London boroughs. She has been instrumental in setting up provision for children with ASD across early years, primary and secondary. She continues to work in schools and with families and undertakes specialist psychological assessments of autistic children and young people.

Maths difficulties are still poorly understood and often have many causal factors. While specific early interventions can and do work well for learners – is it time to consider whether our broad approach to maths teaching is contributing to the problem in the first place?

Many children (and adults) in the UK struggle with maths. Exactly what label is applied to this is currently under some debate. The prevalence of Dyscalculia, a specific learning difficulty, has been estimated at 3-7% although academics are divided on causal mechanisms, definition and diagnosis. Many think of it as one end of a continuum that includes broader maths difficulties and even maths anxiety.

The drive to recognise some of the innate and very specific biological reasons behind maths difficulties is worthy and indeed essential. However, we shouldn’t lose sight of the significant impact that other factors such as teacher-pupil relationships, socio-economic factors and unconscious bias have to play.

And there is, of course, another dimension, which is the method of teaching maths itself. In the UK we often still teach maths in a way that places heavy emphasis on rote learning, including drilling sequences, rules, processes and formulae, from early years right the way through to GCSE. Sometimes we overlook other, deeper routes to understanding that don’t place such a high demand on working memory which puts some learners at a disadvantage.

The social and psychological factors can aggravate maths difficulties

In order to understand the root causes behind why some children struggle, it is important to recognise the role that social factors and teacher-pupil relationships play.

These include;

- Unconscious bias. This is particularly well documented in maths. A study conducted in the US found that when maths teachers were asked to rate pupils’ overall ability they were more likely to judge white pupils as higher achievers than their black or hispanic peers. This is despite previously marking entirely or partially correct answers to an 18-question test without any evidence of bias. Similarly, in a study carried out in Ireland, female primary school teachers were more likely to rate nine-year-old boys as ‘above average’ compared to girls, despite similar academic ability. Bias often means we lower expectations of learners, who then don’t feel supported and fall behind in a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Groupthink” can also negatively impact how we assess and support learners. Researchers from the University of Maryland have demonstrated that such ‘communities of practice’ can result in groups of teachers discarding a more methodological approach to assessing needs, in favour of naturally supporting each other’s beliefs, especially those that place the locus of deficit with the learner. - “Boffin blinkers.” Some teachers are such experts in maths that they cannot remember what it was like to acquire concepts and end up teaching it in a way that misses out key steps. In this situation, the ‘expert in subject matter’ can systematically underestimate the difficulty of the subject matter for the learner – they have their “boffin blinkers” on.

- Maths anxiety. It can take only one or two negative experiences with maths – perhaps when a pupil felt put on the spot – to provoke lasting maths anxiety, which has been shown to overwhelm working memory. Some teachers, particularly those working in Primary schools, can also be anxious about maths, making them gravitate more towards rote learning methods. Students who lack confidence in their teacher’s ability to do maths may also be more likely to suffer from anxiety themselves.

- Socio-economic factors. According to a study in the US, by the time they reach four, children from poorer socio-economic backgrounds may have had considerably less exposure to maths at home than their peers and already. Several UK studies have had similar results (see Fisher et al 2020). Some researchers have pointed to the potential impact of social class on executive functioning as a potential contributing factor to maths difficulties, while others also highlight its link to reading ability and the more verbal aspects of maths.

Is our current approach to maths teaching making difficulties worse?

When it comes to the innate causes behind difficulties, we now know that working memory deficits (including verbal, spatial and visual dimensions) play a significant role. Sometimes the way we teach maths in school places a great deal of cognitive load on precisely these weaker skills, without providing other routes toward gaining maths understanding.

Maths learning works through scaffolding; which essentially means that pupils with working memory difficulties can get stuck on the early foundational levels, unable to move up to the next rung of the ladder.

Here are some common issues with maths teaching in many schools, particularly those following the British or US curriculum:

1. ‘Rote’ learning versus teaching for understanding

Memorisation does have a role to play in maths and there is good grounds for encouraging its use. A study published in Nature Neuroscience, for example, found that memorising the answers to simple maths problems is a key step young children take when developing from counting on fingers to doing more complex sums.

That being said, what we understand as purely rote learning should be balanced with approaches that encourage a deeper relational understanding i.e. knowing why a mathematical rule works. Researchers from the Medical University of Innsbruck in Austria have shown that different parts of the brain are used when pupils are asked to just memorise maths facts, as opposed to working through various strategic approaches to absorb them.

Exploring ways to do maths that rely less on simply drilling maths facts can help level the playing field for those who have working memory deficits.

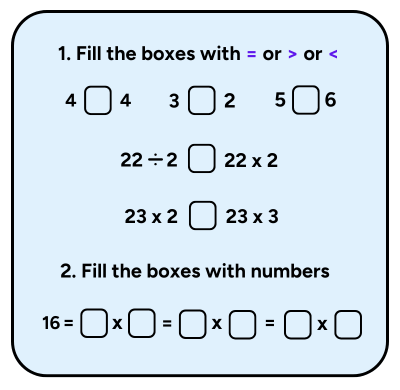

This particularly applies to how we approach sums. Providing learners with pages of calculations such as 14+9 = 23 will not cultivate a rich maths understanding and generate overreliance on the ‘counting on’ method. Rather we should also be challenging them to approach sums using more of an algebraic approach, getting them to place the equivalent, or equals signs and the numbers in missing boxes, in order to complete the sum.

The example below shows what this might look like;

Similarly, at a more advanced level, approaches that promote a visual, less formulaic understanding of things like quadratic equations have recently made headlines and proved popular with some teachers and students.

2. Prioritisation of speed and accuracy over creativity

We have a tendency to praise speed in maths. Often by putting learners on the spot, either by asking for answers to sums in class or using timed tests, we create anxiety which can derail working memory. Yet many of our top mathematicians were not particularly speedy at school, nor are they even as adults. They are however very creative and often highly visual thinkers who were encouraged to explore multiple routes to solving problems.

3. Too much emphasis on arithmetic and not enough on spatial thinking

In 2020 researchers Sorby and Panther found that the performance of fifteen-year-olds on PISA tests correlated highly with their scores on spatial cognition assessments. The researchers concluded that ‘improving spatial skills could be an overlooked strategy to improve student performance.’

Learners with maths difficulties may lack skills in spatial thinking. However the good news is that (contrary to previously held belief), recent research, such as that carried out by academics at the University of Toronto, has found these skills are malleable and can be taught.

4. Lack of confidence and knowledge to select alternative approaches

Many teachers feel like they lack the specific skills to help those with maths difficulties. Training may have been non-existent, or merely scrape the surface when it comes to things like evaluating interventions. This creates uncertainty about bringing more creative solutions into the classroom. Yet having a rotation of different teaching techniques and maths games can have a huge impact on learners; we’ll be investigating this further in later blogs.

Final thoughts

A better understanding of the genetic causes behind maths difficulties should not leave us blind to the influence of social and psychological factors, in particular, teacher-pupil interactions.

The way maths is typically taught throughout the Western world is simply not working for all learners. Many countries, including the UK, have recently attempted to address some of the problems outlined above by adopting the so-called ‘mastery approach’ to maths, used in countries like Japan, Singapore and China. This involves teaching for understanding and intervening as soon as problems are encountered, repeating each small unit of learning until it is securely understood. Although countries like the UK are now encouraging this approach, the extent to which this is uniformly understood, applied and genuinely embedded into teaching approaches varies considerably.

Having a good working understanding of maths is a gateway to higher earning potential and a broader scope of career opportunities. Unfortunately, the routes to achieving this are still blocked by the prioritisation of skills like calculation and memorisation, which can be incredibly demoralising for students with maths difficulties.

What we now know is that there are many more important and creative skills, such as spatial thinking, that go into making a great mathematician and that these skills can be nurtured.

As Marcus du Sautoy, professor of maths at Oxford University writes “even for those with dyscalculia it’s important to remember that mathematics is not simply sums.” Rather, he reminds us, maths is “the language of the universe and it’s one we can all learn to speak.”

Learn more about how to help children with maths difficulties..

Real Training is now offering courses for Primary and Secondary Maths Teachers, TAs, SENCOs and specialist practitioners/teachers/assessors to help build their knowledge and skills to assess and support learners with maths difficulties. Find out more about our courses that help you understand the theory behind maths acquisition and teaching methods and gain the skills to become a specialist maths teacher.

A considerable body of research points to mental health provision being most effective in schools when it is conducted as part of a whole-school approach (Weare and Nind, 2011). This means focusing not just on isolated projects delivered by external experts, but galvanising the entire school community and making mental health an ongoing priority, embedded into the ethos, activities and curriculum of your setting.

To support this, senior mental health leads need to have a good understanding of both change management principles, particularly those endorsed by the EEF (Education Endowment Foundation), and the latest mental health best practice.

Below, we’ve illustrated some of the tactics a senior mental health lead might be focusing on and how they fit into the eight principles of the whole school approach as defined by Public Health England. Although tactical interventions are only relevant when considered in the context of an action plan developed for each setting, there may well be ideas that are helpful for you.

LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT

1. Set up staff working groups for mental health and wellbeing

This allows you to establish clear roles and responsibilities and enable staff voices to be heard. A working group provides a clear link between pastoral leaders, mental health first aiders, teaching staff, SENCOs, school nurses and family liaison officers.

2. Create a student-friendly version of your mental health policy

Asking a group of pupils and staff to create a student-friendly version (or a series of videos) of your updated policy, raises awareness, encourages a sense of inclusion and makes your policy more accessible to all students.

STUDENT VOICE

3. Strengthen your student council

Giving your student council a dedicated role in wellbeing initiatives such as leading anti-bullying programmes and wellbeing awareness days gives them a sense of agency and increases the likelihood of engagement. Consider committing to regular “you said, we did” assemblies and ensuring all student groups with responsibility for wellbeing (e.g. LGBTQ+ groups.) meet regularly.

4. Launch a Wellbeing Ambassadors programme

Wellbeing ambassadors receive specific training enabling them to provide peer mentorship support and can play an active role in promoting wellbeing initiatives.

STAFF DEVELOPMENT, HEALTH AND WELLBEING

5. Identify gaps in mental health training

A Google poll can be a helpful way to identify where staff feel there are gaps in training, allowing you to devise a plan and a budget for both universal and focused interventions e.g. bereavement or trauma-informed practice.

6. Review staff mentorship and supervision

Appointing a dedicated CPD leader for mental health means they can coordinate the logistics for the training. This leaves SMHLs free to review the mentoring in place for staff so they know who to approach when they feel out of their depth or if a child discloses something that the staff member needs to talk to someone else about.

IDENTIFYING NEED AND MONITORING IMPACT

7. Evaluate existing targeted interventions

Using a more structured way to assess targeted interventions for example The Art Room, (group therapy) or the effectiveness of ELSA support according to the Assess-Plan-Do framework helps you track and evaluate their impact. This might include using online assessment tools such as the Boxhill profile.

8. Improve general wellbeing questionnaires and feedback forms

Including some questions that are generated by students captures often captures feedback that might otherwise have been missed, as does more open ended feedback from focus-groups. All of this information should be stored in one place to be filtered into a plan of action.

WORKING WITH PARENTS, FAMILIES AND CARERS

9. Launch wellbeing drop-in sessions for parents of children with SEND

Establishing regular drop-in sessions can provide effective early support, increase awareness of masking in school and build stronger parental support networks. Topics might include managing anxiety and school arrivals, guidance around emotional regulation, or tips on how to prepare for transitioning years.

10. Create a digital and face-to-face strategy for parent education

Creating a wellbeing hub on the school website as well as offering in-person sessions can help parents with their own wellbeing, as well as encouraging continuity of techniques practiced at home and school. You might also consider a dedicated wellbeing app for parents and children.

ETHOS AND ENVIRONMENT

11. Embed SEMH strategies e.g. Zones of Regulation

Driving a whole-school approach to emotional regulation using techniques such as Zones of Regulation or trauma-informed practice will help lay the groundwork for better metal health. Actively incorporate this into pedagogy and best practices around rewards and consequences in school and make sure it is being learned not just by rote, or displayed on a couple of posters, but as a tool that staff regularly model and children actively use.

CURRICULUM, TEACHING AND LEARNING

12. Revise PSHE policies and documentation

Doing this will ensure all aspects of mental health are being covered effectively and in line with the latest guidance. You may also consider surveying students to understand their views on current PSHE lessons and whether they want to see additional topics covered.

PROVIDING TARGETED SUPPORT AND APPROPRIATE REFERRALS

13. Establish a network of local providers

Producing a directory of local providers and understanding exactly what services they offer and their typical waiting times will help staff make more informed referrals and cut down on admin time.

14. Create a mental health referral toolkit for pupils

Creating a student-facing resource that all pupils can easily navigate will reduce some of the barriers and provide direct access to clinical or community support. This should clearly signpost services in the community e.g. for young carers.

In conclusion

The tactics every SMHL chooses to implement will vary hugely depending on your pupil mix, what type of setting you work in, the resources available to you, the delivery partners you work with and the immediate mental health priorities of your staff, pupils and parents.

While a minority of tactics might be able to be picked off quite readily, most are lengthy projects in themselves and we often recommend that the SMHL selects just a few areas to focus on each academic year. Our senior mental health lead training courses include one-to-one coaching from an educational psychologist who understands the context and challenges of driving meaningful change within a school environment.

Further reading

Find out more about the whole-school approach to mental health

Watch a case study video: A whole-school approach to health in a Yorkshire primary school

New to the role? Read former SMHL, Andrew Chadwick’s 8 top tips for success for senior mental health leads

Beverley Williams is one of our delegates here at Real Training. She has had an expansive career, influencing the lives of many young people with SEN. Not only has Beverley completed multiple courses with Real Training and gained a vast amount of professional knowledge through SEN and safeguarding roles, but she was also diagnosed with Aspergers at around 50 years old.

We thought it would be useful to share Beverley’s story, not only for those delegates looking to have an impact but also for anyone on the autistic spectrum who may be looking for some advice.

By Andrew Chadwick is a former Headteacher and SMHL, and is currently Safeguarding, Ambition and Inclusion Lead at Focus-Trust. In this article he gives some essential advice for anyone new to the senior mental health lead role.

Article originally published in Headteacher Update Magazine 11.03.2024 – accessible here

The senior mental health lead role is challenging and there never seems like enough time in the day to do it justice. However, the role is fundamental to the positive wellbeing of pupils and staff in school.

In education, we are all taught about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and it is worth reflecting on just how important things beyond physiological requirements, such as a feeling of belonging and wellbeing, truly are. Every child deserves to have this at school. However, it takes someone who can lead whole-school change and influence every layer of the school community to begin to go about meeting these needs.

Every setting has its own unique circumstances and challenges. That being said, there are some key pieces of advice I would offer to all those who are new to the role of senior mental health lead to help them hit the ground running, including tips to help you get the most out of the government-funded training.

Don’t try to take on too much, too quickly

One of the biggest challenges I faced when I first started in the role turned out to be self-management. Like many leads, I wanted to do everything straight away, but it is really important to audit provision to identify a few focus areas each academic year and go through a structured change management process. You simply can’t rush ethos change if you want it to be meaningful. This is where the senior mental health lead training course can be particularly useful.

Be brave and have difficult conversations

It can be incredibly challenging to talk about certain topics, such as suicide, especially in primary schools and many staff were deeply concerned about the possible effects. However, it’s far more risky and scary not to have these conversations – it just needs to be done under the proper framework and with the right training (and communications) in place.

Don’t overlook the importance of parents’ mental health

Some way into creating an implementation plan for the year during my senior mental health lead training course, I realised that we were going to need to provide some sort of provision for parents themselves in order to really make an impact. The cost of living crisis and the pandemic exacerbated many mental health problems which, in many cases, are being passed from parent to child.

At my school, we sought to actively include parents in wellbeing initiatives as well as offering programmes like the mums’ wellbeing groups and later one for dads as well. There’s so much stigma around mental health that you can’t go in all guns blazing, sometimes the softly, softly approach works better.

For example, we’re now piloting parents’ cookery classes at another school in my trust as a means to encourage people to socialise and think about their mental health. The hope is that people come for the food and then while they are there we will have a guided discussion on a different wellbeing topic each week.

Let staff have a say in designing new initiatives

We wanted staff to champion wellbeing initiatives everywhere throughout school, as well as being able to benefit from them themselves. To achieve this we consulted all staff on things like the Zones of Regulation and ended up adapting the strategy and making our own resources to suit the needs of our setting.

Setting up a working party for social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs was particularly effective and we found techniques like the “rich picture method” incredibly useful to collate ideas and identify areas of weaknesses.

Think about your gatekeepers

When it comes to making changes to staffing, systems and processes, don’t overlook your front-of-house teams who may be the first point of interaction with parents. They need to be approachable and let you know when vulnerable individuals need help so you can drop everything to be there.

Consider the right mental health training, for the right staff, at the right time

I made it clear in my action plan that I didn’t think a whole-staff approach to training was always appropriate. Teachers’ workloads can be so great that they can simply be overwhelmed and not retain additional information well. When it came to things like trauma training we trained only those who needed it, when they needed it.

Don’t underestimate the power of supervision

Helping pupils with more significant needs can have an impact on staff. Often, especially in smaller primary schools, we just assume that we see each other every day so can check in with each other, but there’s a real power to more structured supervision. We’re currently developing triads of schools that can collaborate across the trust to provide this enhanced support.

You can read more about Andrew’s approach to trauma training in his interview with Educational Psychologist Joanna Wood.

Take advantage of senior mental health lead training

Government funding for the senior mental health lead training is available up until the end of March this year (DfE, 2024). It is not certain that it will be renewed every year so apply while you can. Look for a course that’s flexible and practice-led so that it helps, rather than detracts, from your day-to-day workload and it becomes part of what you need to do.

The course I took was led by educational psychologists at Real Training and the tutor support was excellent. It prompted me to become a lot more strategic in my whole-school approach.

Reflection was absolutely key to the success of my projects. The senior mental health lead training required me to go through a reflective journal. Although at first, I must admit I was a little sceptical, it turned out to be a really powerful tool, alongside regular feedback from my tutor.

Final thoughts

The senior mental health lead role is one of the most crucial in our schools. Of course, finding time to devote to doing the role well can be hard, but remember that the impact you can have across school and on children’s lives is nothing short of phenomenal.

Read more

Find out more about senior mental health lead training and which course is right for you

Watch Andrew’s full review video of Real Training’s senior mental health lead advanced award

Read the full case study to find out more about the impact of Andrew’s action plan at his primary school

Kara Satterley – Senior Mental Health Leadership Certificate

Kara Satterley is Deputy Headteacher and Senior Mental Health Lead at Blean Primary School, an OFSTED outstanding school based in Canterbury.

She has recently completed her senior mental health leadership certificate and shared her experience of how it has made a difference in her school.

What made you choose the Real Training senior mental health lead course over other options?

The online approach with live sessions, the quality of tutoring, and the time to put actions into place and learn as you go along were the main things that attracted me to this course. The fact that everything could be completed online supported both my leadership commitments and my work-life balance.

What was your experience of learning with Real Training?

My experience was excellent. Communication was strong from the get-go and staff were really supportive, particularly when I needed to move cohorts. The training was thorough, relevant, and detailed and my tutor was incredibly knowledgeable and supportive. I also really enjoyed the live sessions; it was so helpful to discuss things with other delegates and learn from others. The online approach provided the flexibility required for me to manage my other leadership roles in school, whilst being able to develop my skills as a new SMHL. The pacing between sessions was helpful, as this enabled time to put actions into place and then reflect and share findings with other delegates.

How has the SMHL course helped make an impact at school?

The course helped to embed the SMHL role in school, with the output being a clear action plan to support pupils. This has fed into our whole school plan for this year. Mental health and well-being are at the forefront of all we do and underpin so many of our other changes at school.

We have recently achieved the WAS award (Wellbeing Award for Schools) and completing the course went a long way to help us change our practice, strengthen our whole school approach, and gather the evidence required to put together a successful submission.

How has the course helped develop you as an educational professional and what do you hope to achieve with your new knowledge/skills in the future?

I feel more confident leading mental health and wellbeing at school at a strategic level. Decisions have informed the school plan and are underpinned by research. We have formed a team with distinct roles and responsibilities to support mental health and well-being across the school to support our staff, pupils, and families.

Lastly, what are the top three things you were looking to do within your setting, since completing senior mental health lead training?

- Achieve wellbeing award (WAS award)

- Form a team to support mental health and well-being to support pupils, staff, and families

- Use knowledge to have dedicated sections of the school plan to ensure strategic change linked to improving mental health and wellbeing

As part of our commitment to the continuous improvement of our courses and to ensure the most effective learning experience for our delegates, we regularly review our programmes. Our goal is to equip our delegates with the necessary skills and knowledge to make maximum impact in their settings.

We are delighted to announce that we have just released an update to our popular Certificate of Competence in Educational Testing online course. The updates include:

- New multimedia content, in the form of videos and animations of key concepts, make the content more accessible and interactive. See an example below from the section on the scaling and standardisation of psychometric tests

February 2025: Latest Update

The SMHL Government Funding Grant application has now closed. However, you can still join our courses without funding. Please explore our Senior Mental Health Lead Certificate and Senior Mental Health Lead Advanced Award to find out more.

Senior Mental Health Lead Training – how to apply for grant funding

February 2024: The Department for Education (DfE) has announced an additional year of grant funding for senior mental health leads, for all state-funded schools and colleges in England. They will also be offering second grants for eligible settings who have used their funding but whose Senior Mental Health Lead has left.

‘Second grants can be claimed by eligible schools and colleges if the senior mental health lead they previously trained left their setting before embedding a whole school or college approach to mental health and wellbeing.’

Eligible settings can apply for a senior mental health lead training grant. Second grants are available for settings who have used their funding but whose SMHL has left.

This article provides information on how to apply for grant funding for the Real Training Senior Mental Health Leadership courses.

We are pleased to share that further funding available for senior mental health lead training, means that up to two thirds of eligible settings will have the opportunity to benefit from the training. Applications are now open, and in this article, we guide you through the steps to complete the process.

Step 1 – Read the guidance for grant funding to ensure eligibility

The DfE has published a comprehensive guide to applying for grant funding. Initially, we recommend you visit this page, which offers a useful overview of topics such as what the grant must be used for, eligibility criteria when to complete the submission and so on. It will also provide information regarding creating a ‘DfE Sign-in account’ which is necessary in order to access the form.

You can also visit this page which will offer more information on the conditions of the grant and application guidance. We highly recommend you read all of this information to avoid submission errors that could delay or invalidate your application unnecessarily.

Note: if you are not eligible for funding, don’t worry as we have non-funded places available too. Our courses are just as relevant to those working in non-state or international settings as well.

Step 2 – Decide on the course you wish to apply for grant funding

In order to receive the grant payment, you will need to confirm to the DfE which training course you have chosen.

At Real Training, we offer two DfE quality-assured Senior Mental Health Leadership courses. Click the links below to visit our course pages and learn more or visit our guide to senior mental health lead training overview page.

Senior Mental Health Leadership Certificate (SMHLC) – aimed at those who are new to a Senior Mental Health Leadership role or are aspiring to become a leader in this area.

Senior Mental Health Leadership – Advanced Award (SMHLAA) – aimed at those who have some experience in the role, and have some existing training in mental health leadership.

If you are unsure which of these is best for you, then please don’t hesitate to get in touch with one of our experienced course advisors who will be happy to help, either by email info@realgroup.co.uk or by phone on +44 (0)1273 35 80 80.

We encourage you to apply for a grant BEFORE you book a course if your place is reliant on this funding.

Step 3 – Collate information for your setting in preparation for application

It is important to ensure you have the relevant information to hand in and that certain conditions are met before commencing the application process. This includes, but is in no way limited to:

- Having a commitment from your setting’s senior leadership team to develop a whole school, college or centre approach to mental health and wellbeing

- Details of your senior mental health lead, who will receive the training in 2023 to 2024 financial year, to oversee your setting’s whole school, college or centre approach

- Authority to submit a claim for this training grant on behalf of your educational setting

Having this information readily available will enormously reduce the time it takes to apply and helps ensure correct information is provided first time.

Step 4 – Complete the application form

Once you have all of the necessary information required, you can access the form here. At this point, you will need to log into your DfE account. It is important to check all the details that the DfE holds for your account – you can complete this form if any of them are incorrect. You will then be guided through the application form, step-by-step.

Once complete, you will be asked to agree to the declarations set out in the grant terms and conditions. You will then receive an email of confirmation, containing your claim reference. It isn’t possible to make amendments to the application form once submitted. However, if errors have been made or circumstances change, you can submit another application, the details of which will be used, and previous applications disregarded.

Step 5 – Book your course

Once you have received confirmation of your grant, you can visit our booking form to book your place on one of our Senior Mental Health Leadership courses.

Step 6 – Confirm your chosen course with the DfE

The DfE will ask you to complete a further form to confirm that you have booked your chosen course. This form should appear right after completing the first form. This will enable them to authorise payment of your grant.

Key dates:

- Complete application form 1 by 31 December 2024 to reserve a grant

- Book your DfE quality assured training course by 31 January 2025

- Start your training course by 31 March 2025.

Improving mental health and wellbeing has risen to the top of the agenda for all schools. One powerful way to do this is to strengthen the role of pupil voice within your setting.

Demonstrating to young people that their views and experiences matter improves their sense of belonging and helps them feel like valued members of the school community. It also means that wellbeing initiatives are more likely to become part of the fabric of school life.

In practice, achieving this requires more than handing out surveys designed by adults once a term. It also means going further than just asking the usual suspects for their opinions. Rather, there should be designated ways for all children’s voices to be heard when they feel they need to express something.

In this article, we highlight examples of how primary and secondary school pupils can take the lead in wellbeing initiatives, and some tips to make gathering pupil voice more inclusive.

Including Pupil Voice in Your Whole-school Approach to Mental Health and Wellbeing

Pupil voice is an essential part of a whole-school approach, below are some practical examples of how schools are approaching this.

Wellbeing ambassadors; groups of children trained to promote wellbeing throughout school as well as feeding back ideas and opinions. They can also offer a listening ear to younger children who may feel more nervous speaking to adults. Various training schemes exist, including those from Worth-it and Eikon.

In primary schools ambassadors might co-produce, lead or help to coordinate things such as:

- Kindness trees

- Motivational message displays

- Wellbeing assemblies

- Happiness walks

- Lunchtime music clubs

- WOW Wednesdays with lunchtime games

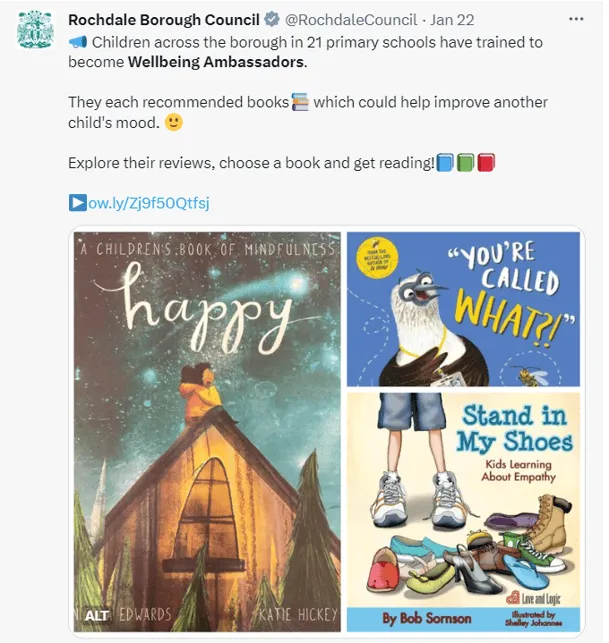

Take a look at what younger wellbeing ambassadors are doing in Rochdale for example;

In secondary schools there is even greater scope for the ambassadors to lead initiatives such as;

- Anti-racism campaigns (e.g. leading a ‘spotlight on identity’ session during house mornings)

- Exam anxiety drop-in sessions

- Lunchtime “walk and talk” mentoring sessions for pupils in transitioning years

- Wellbeing cafes and hubs

- Co-designing stress flashpoint surveys and creating management tips

- Co-creating guides to mental health and wellbeing

You might also want to consider trust-wide initiatives such as the one below at Belle Vue Girls’ Academy;

Student councils; are a great way of getting feedback on any issues in school that touch on mental health. The disadvantage is that they have a broad remit of issues to tackle and only a small number of pupils can get involved and they are usually voted in by peers. Some school councils – even in secondary schools, still have their agendas set entirely by adults, which limits their ability to really get to grips with issues young people want and need to explore.

Anti-bulling Ambassadors/Young Carer Groups/LGBTQ+ groups/ Young Sports Ambassadors; there are lots of programmes and groups that may already exist in your setting that have an important role to play when it comes to voicing opinion and actively shaping mental health and wellbeing initiatives.

Meet and greeters at school gates/peer mentors; can help listen to children who are feeling worried and act as a voice for quieter pupils. They also can provide feedback on how they think wellbeing initiatives are working. Just like the wellbeing ambassadors, however, they should not be the first point of call for children already requiring mental health intervention and they should know how to signpost children to adults should they happen to disclose anything significant.

Surveys; provide a quantifiable way of doing a temperature check on wellbeing across the school, as well as seeking feedback on initiatives. By planning ahead you can segment data and drill down into which groups are feeling distress more often, to bring focus to wellbeing initiatives. The limitation, of course, is that bias can enter question design, surveys rely on children being able to comprehend the question and they don’t allow for open-ended discussion. Certain types of wellbeing surveys might benefit from pupil input on which questions to ask – particularly for secondary schools.

In practice: Students from Boulevard Academy have become trained Young Evaluators. They were able to make suggestions which the school actioned including adding mindfulness sessions at the start of PSHE lessons, extending LGBTQ support beyond PRIDE week, improving signposting to wellbeing support and frequency of visits from external providers such as Barnardos, Lifeskills and Advotalk. They have also helped to launch a wellbeing app and accompanying resources.

In practice: Carwarden House Community School, a LAN special needs secondary school, has recently trained nine mental health ambassadors who meet regularly with their Senior Leadership Team and manage campaigns to improve wellbeing and stress management across the school. The school has recently introduced ‘Hub Clubs’ for each Key Stage which their ambassadors autonomously lead and organise wellbeing activities for. They also have a vibrant student council that regularly meets with the SLT.

In practice: Brighton Hill Community School used both focus groups and questionnaires to collect student voice on wellbeing. The results identified a need for more social, face-to-face support and signposting, leading to the creation of their wellbeing square. At lunchtime, pupils can visit zones that include, Freedom2b, where students can discuss how to embrace diversity, Q-space for personal reflection, the YC space, which is to recognise the role and existence of young carers, and the wellbeing space. Student ambassadors are actively involved in providing support.

6 Ways to Make Collating Pupil Voice More Inclusive

Many of the ways we listen to student voice can inadvertently favour children who are more confident or articulate than their peers. This can leave children with EAL, SEND or from poorer socio-economic backgrounds at a disadvantage – precisely the kind of children who may be more at risk of poor mental health. So how can we ensure their voices are heard? There are no easy answers, but a few things to consider;

1. Help student councils become more aware of the voices of vulnerable learners

Mandating the inclusion of representatives from minority backgrounds or with SEND on your council could be seen as tokenism and detracts from the democratic process. You could, however, evaluate the ways pupils can apply. Can pupils submit videos rather than written statements? Can they be anonymously transcribed and read out by adults rather than requiring pupils to stand in front of peers? Do all positions on your council require reps to speak in front of the whole school? You could also help school councils to meet regularly with pupils from minority groups, children with SEND, or adults who could convey feedback on behalf of the pupils they support.

2. Encourage a variety of children to become wellbeing ambassadors or council representatives

You might want to have one-on-one conversations with pupils who you feel might be a good fit for the role ahead of explaining the scheme to the whole class so they feel encouraged to put themselves forward. When opening up a vote, you could consider asking pupils questions like “Who do you feel would be a good listener” so it’s not just the loudest children that get picked. Confidence-building workshops can also help pupils prepare for the role.

3. Find less formal ways to make pupil voices heard

Asking for feedback on wellbeing initiatives in circle time (primary) or tutor time or PSHE lessons (secondary) is a good way to make it less intimidating for pupils to contribute. A hands-up approach might not always be best here, consider things like the Kagan Cooperative Learning approach.

In practice: Winton Community Academy runs Focus Fridays where they select a random group of students each week and bring them together to discuss wellbeing.

“The open discussions on Focus Fridays gave context rather than just questions on an audit, and we thought it to be better than the same students all the time, such as on a council.”

Justine Sebon, Student Welfare Manager, Winton Community Academy

4. Make use of multimedia, suggestion boxes and alternative channels

Allowing pupils to record and upload messages to their teacher in a listening corner, or using free software to upload video messages offers alternative avenues for pupils to voice their feelings. If you aren’t already using them, consider suggestion slips or self-referral boxes or “things I want my teacher to know” boxes in primary schools. Many schools now actively avoid calling them worry boxes to reduce any potential stigma.

In practice: At Marwood Primary School in Devon mental health ambassadors are actively engaged in wellbeing initiatives. Children can write their worries down (independently or with the help of an adult) and post them into boxes and the ambassadors reply back with suggestions to help. They also wear rainbow lanyards and have their pictures displayed around school so that everyone, including students with SEN needs, can easily recognise them and seek them out for help.

“I think that this system has made it easier for our pupils to have a voice – sometimes they just feel more confident talking to an older child than they might do an adult.”

Sharon Sanders, SEND Practitioner, Marwood Primary School

5. Make sure surveys are accessible

Depending upon the severity of need, children with SEND will require different adaptations, ranging from stripping out complex or open-ended questions through to using symbols and pictures. Guided questionnaires with one-to-one support from adults can also help, as can compatibility with assistive technology.

6. Help children who struggle with vocabulary to express themselves

Pictures, symbols, visual clues and sign language can help a child with SEND express their enjoyment of a particular wellbeing initiative, for example, whether they enjoy a wellbeing walk with their friends. LSAs should also feed feedback on any well-being initiatives they think need to be adapted so that pupils with SEND can take part.

More generally, pupils should also be encouraged to express their feelings and wishes through a variety of means. Many educational psychologists use techniques like the three houses, genograms, and “all about me” profiles, while family support groups can also be a good way to listen to children’s views with the support of others.

In practice: Thornbury Primary School has a high number of pupils with speech and language difficulties. Children have individual ways of signalling that they are seeking a conversation, such as using traffic light cards, putting an item on the teacher’s keyboard, or sharing a journal. They also use colour-coded speech bubbles, worry boxes and ‘Animal Aces’ which are personas that bring the school’s values to life.

“Pupil voice is not something we find out about, as leaders, simply in termly monitoring activity. Pupil voice is implicit in every part of the school day, from a passing comment in the corridor to a debate in the classroom.”

Claire Hardisty, Headteacher, Thornbury Primary School writing in Teacher Times.

Ask, Listen, Act, Feedback

Pupil voice strategies will only be successful if schools can demonstrate they are acting on the information disclosed. Staff need to be ready to listen to mental health concerns, governors need to make space on agendas for listening to pupil viewpoints on wellbeing and school leaders need to explain to pupils why some ideas are implemented over others. If you don’t already have a wellbeing link governor you might consider appointing one and ensure that this person is looking closely at pupil voice.

“You said, we did” assemblies are also useful feedback mechanisms, as are form tutor sessions, newsletters and noticeboards. Finally – don’t forget to update your mental health policy, school action plans and child-friendly versions of these documents. Doing the above will help lay the groundwork to align staff, systems and processes with pupil voice so that it starts to become embedded into your school ethos.

Further Resources

- Confidence-building worksheets: (Free resources from ELSA) available here

- Five Ways to Wellbeing – activity ideas for wellbeing ambassadors (Eikon) available here

- Primary/Secondary Children’s Mental Health Week Resources (From Place2Be) available here

- Best practice for school councils: (A guide issued by Involver, a social enterprise) available here

- How to stay mentally healthy during exams: (Resource from YoungMinds charity) available here

- Creative film workshops for young people (HeyDey Films) more information available here

- Tips for helping autistic children develop a sense of identity: (Raising children Australian parenting site) available here

- Complete guide to the Senior Mental Health Lead role (Real Training) available here