Imogen Barber |

December 2, 2024

We will all have exposure to significant events in our lives that could be classified as ’traumatic’. Some examples might be an unexpected bereavement or death of a significant other, being a victim of violence or crime, or having a life-threatening illness. For many of us, these will not be consciously remembered or have an impact on our behaviour. However, when these are experienced by young children and prolonged over time they can have an influence on the developing brain, affecting children’s physical response to stress and framing their perceptions of themselves and others.

In school environments, trauma often presents as challenging behaviour, which can escalate to the point of exclusion. Yet with the right understanding and frameworks in place, this need not be the case – school can also be a place where children find a sense of belonging and trauma begins to heal.

In this blog, we’ll take a look at how trauma impacts young people, run through some of the key things to remember about trauma-informed practice and wrap up with some advice for senior leaders as they embed a whole-school approach.

The Trauma-informed Approach: 8 Key Takeaways

1. Trauma can affect children’s “window of tolerance”

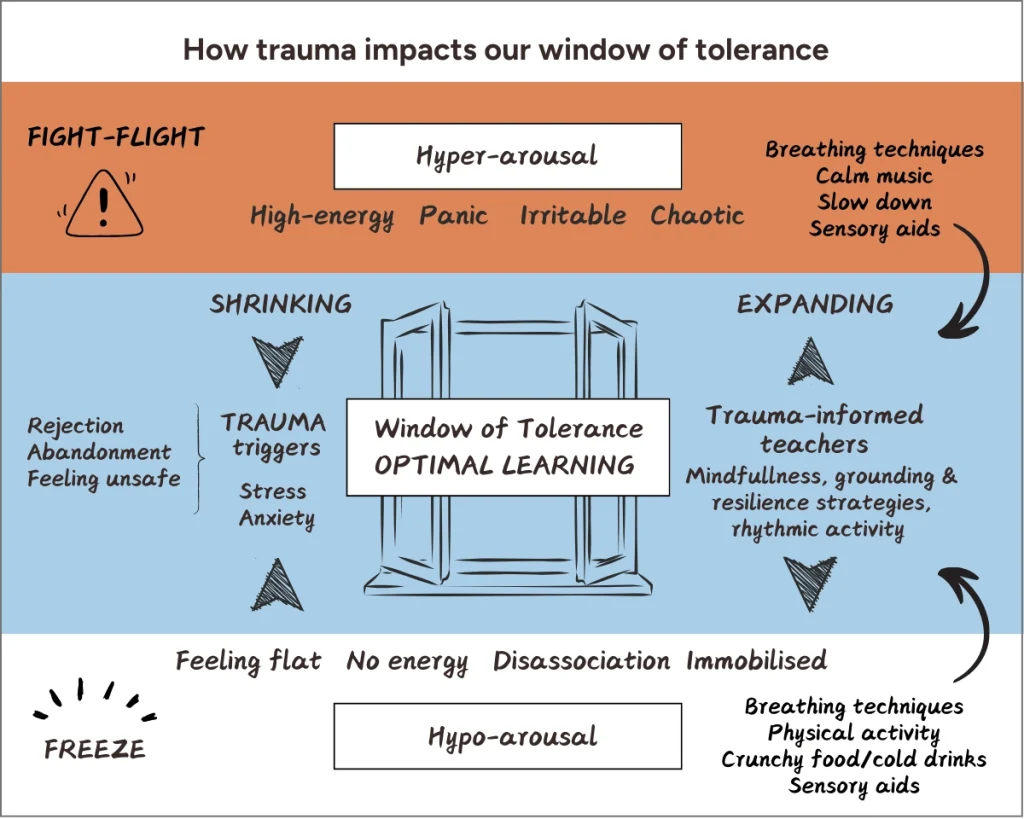

We all have what Dr. Dan Siegel describes as a “window of tolerance” – essentially our capacity to comfortably cope with external stimuli and regulate our own emotional response in return. Most of the time we remain comfortably within our window, particularly if our life experiences are typified by security and stability. When difficult times take us to the edge we can usually bring ourselves back to a state of equilibrium.

Young people who have experienced trauma, however, may have a much narrower window. They can also be tipped outside it with less provocation. This can generate hyper-arousal – the child in the playground who is causing explosive arguments and ‘fallouts’ with peers, or swearing at adults at seemingly minor incidents. It can also result in hypo-arousal – the child who is emotionally withdrawn, incapable of concentrating and fearful of being left alone with their own thoughts.

In both scenarios, we need to help these children ‘come back into their window’ before we can problem-solve with them.

2. Regulate the young person’s physical response first

The body often has a marked chemical response to experiencing stress, releasing hormones that impact our physical state (i.e. the fight/flight or freeze mode).

A trauma-informed framework means first supporting pupils by calming their physical state. Sarah Norris is an educational psychologist and mental health programme leader at Real Training. “Very often in schools, our response to pupils is to talk to them and to try and apply logical reasoning in a situation,” she says, “but actually we should be limiting our language use and trying to work out what they need to help them physically calm down”.

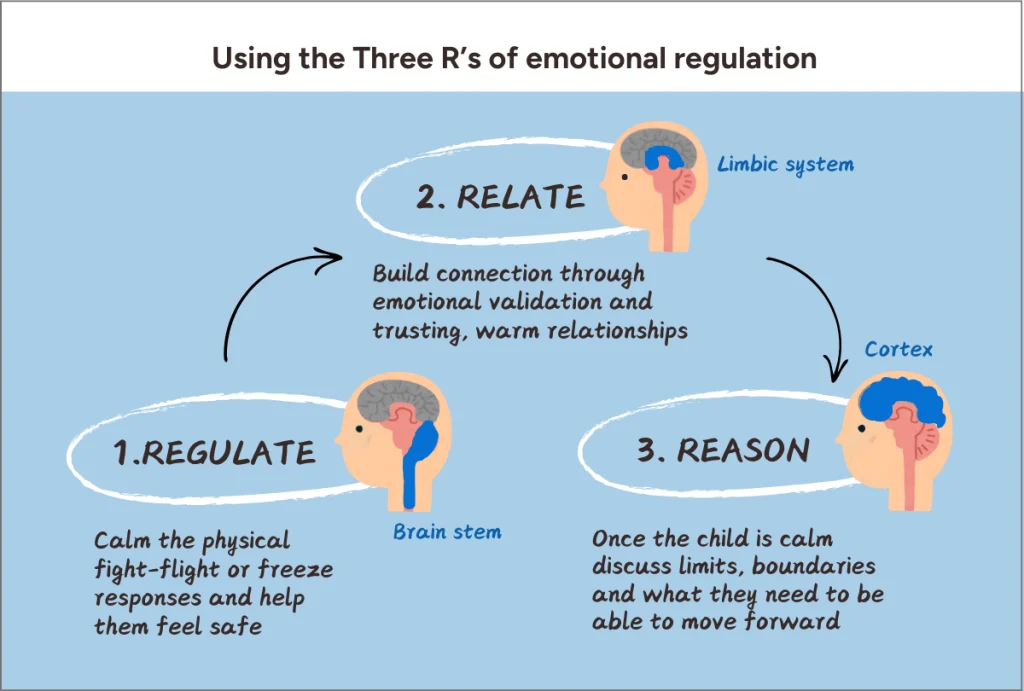

The idea that we need to tackle physiological regulation before engaging in higher-level cognitive tasks such as reasoning, has been described in depth by American psychiatrist Dr Bruce Perry. His ‘Regulate, Relate and Reason’ framework highlights that different areas of the brain have to be engaged in the right sequence to help children in moments of extreme stress or emotional dysregulation.

The first step in the process is to “regulate” the body and this triggers a feedback mechanism to the brain stem to stop it from producing ‘stress hormones’. We can do this by using strategies that focus on pupils’ physical modalities. What works for one will not work for all but some examples include;

- Deep and slow breathing; finger breaths or ‘breathe the square’.

- Sucking, chewing or drinking; cold drinks, crunching ice cubes, eating apples/carrots.

- Physical movement; star jumps, walking a circuit, running laps.

- Listening to calming music.

- Sensory play using water, sand, and slime.

- Heavy pushing, pull-ups, monkey bars.

3. Dysregulated adults cannot help dysregulated children

The ‘regulate’ element in Dr Bruce’s model applies equally to the adults in the room as it does to students. Acknowledging your physiological or emotional response to a child’s behaviour means you can be in a better place to respond.

Take a mini-pause before you respond to the behaviour and remind yourself not to react emotionally. “It’s all about tapping into your compassionate response,” says Sarah, “it can be very hard not to react in the heat of the moment, but this is what we must try to do.”

If possible, adopt a neutral body posture, think about your facial expression and tone and avoid communicating with commands and using gestures such as pointing that could come across as threatening. Sarah also recommends trying out things like reducing the tension in your shoulders, unclenching your hands, being aware of personal space and giving the young person time to think about what you’re saying.

4. Relationships are key: Everything hinges on trust and safety

Once both the adult and young person are regulated, we can move onto the next stage – relating to the child. This will be most effective if you’ve already laid the groundwork and established yourself as an adult who is physically and emotionally available.

“Adults need to be the safe harbour in the storm,” Sarah explains, “if you’ve got a child who’s hiding under a desk, or swearing at you in class, that behaviour is communicating something to you. Most likely about their past experiences. What they’re saying to you is; “I need to protect myself. I don’t feel safe.”

You can establish a sense of psychological safety in class by;

- welcoming children into the classroom every day (morning meetings in secondary). If you can, make it special, and make it personal to the individual.

- setting boundaries and limits, having clear expectations

- being mindful of your body language and tone of voice

- establishing clear routines – schools often use visual timetables but it can be helpful to give more structure to specific periods of time so students know what to expect. For example, structuring a literacy session so that pupils know it will start with a carpet introduction, followed by partner work and discussion and then they will start a writing project.

- taking time to listen to the pupils in your class, showing genuine interest in them and being non-judgemental in your responses

5. Children need to be seen and heard

A key part of relating to the child involves validating the young person’s life experience and connecting with them in the moment. “Often we are afraid to name the emotions or feelings that the young person is experiencing because we think that by shining a light on them they will intensify,” says Sarah, “but actually the reverse can be true. By naming feelings we show empathy and understanding, this can help diffuse things.”

It’s ok to show the young person you don’t necessarily have the answers. A trauma-informed response communicates “I’m trying to think about why you might be feeling this way. Can you help me to understand?”

WINE is a great tool that can help us think about using language that connects rather than shames;

- I wonder if you kicked that over because something has upset you today?

- I imagine that you’re feeling angry and maybe a bit lonely because you wanted to partner with Amy but she’s chosen someone else. I know things are tough for you right now – is there anything else going on that’s making you feel a bit down today?

- I notice that you were speaking loudly and are now breathing quite fast – would you like to go outside and get some fresh air, would that help?

Empathy should always be shown – that must be tough but let’s work through this together. Shall we try…

6. “What do you need to move forward?” Reflecting with pupils should be focussed on meeting their needs.

Reasoning is an important final stage in the trauma-informed approach, but can only happen once you’ve gone through the other steps. Reflective conversations can occur with a trusted adult or someone who is not directly involved.

There are many tools that support this within a more traditional behaviour management approach and these often have common themes around; what ‘triggered’ the behaviour, what is the unwanted behaviour and what were the consequences. Pupils are then invited to consider how they will behave differently next time.

Within a trauma-informed approach, however, these reflections are always guided by the principle of meeting the child’s needs i.e. How can we support you? What do you need to do next time?

7. It’s not about excusing bad behaviour

“The emphasis should be on the behaviour we do want to see, but it’s ok to point out the boundaries,” says Sarah. Indeed, she emphasises that “boundaries are one of the essential components for feeling safe and able to self-regulate.”

Let’s take an example. What happens if a young person, when asked to do something in class tells you to F*** off. How should you respond? “It’s highly likely that that pupil is struggling with cause-and-effect thinking right now, so the traditional hierarchy of sanctions such as time out, detentions and exclusions will have a limited effect,” Sarah says. “They aren’t going to change the behaviour in the long-term and could just escalate it.”

However, it is ok to emphasise natural consequences that are more closely linked to the behaviour. “Once you have communicated with Child Z “I get you and I hear you”, acknowledged their emotions and helped them calm down then you can absolutely follow up on their use of language,” Sarah says. The student might repair the relationship by writing a letter or having one-to-one meetings, where they acknowledge the impact of their actions on other students’ learning and on the teacher.

8. Think of self-care as part of putting in the work

Sarah describes self-care as “the most important and often overlooked principle” of trauma-informed practice. The old adage of putting on your own oxygen mask before helping others is especially true in this instance,” she says, “if you run out of oxygen you are no help to anyone.” Some things that she suggests can help include;

- Carving out time to put yourself first – plan time in the day to use breaks more effectively, put away the tech and step outside in fresh air and daylight.

- Practising self-compassion – think about how we can be our own best friend, celebrate wins, and reframe setbacks as opportunities.

- Seeking peer support – regardless of whether children are actually describing traumatic events, sitting with a young person’s emotions can take an unexpected toll on the adult. Having trusted conversations with a peer can help with perspective as well as sharing ideas when things aren’t working.

Some things for Senior Mental Health Leads to think about

Promoting staff wellbeing

This might include opportunities for flexible working, duvet days, and accommodations made for staff during particular pressure points in the school year. Consider whether the supervision on offer is adequate as well, particularly for staff who have pupils in their classrooms who are known to have suffered ACEs (adverse childhood experiences).

Establishing sustainable change

In order to bring about any kind of sustainable change in schools it is important to think about your school ethos and values. There needs to be synergy between the tenets of trauma-informed practice and your current ideals, principles and projects so that it is integrated with the rest of your mental health initiatives and wider curriculum.

We cover strategic approaches to managing whole-school transformation projects, in our senior mental health lead certificate course, which also provides further information about trauma.

Thinking about wider policies

It’s not just your behavioural policy that needs to be updated, principles like empowering young people and acting with compassion need to be reflected across your values and demonstrated in your school ethos. For example, how you incorporate pupil voice into PSHE lessons, how you lead your staff and the qualities you look for in new hires.

Depth/frequency of training required

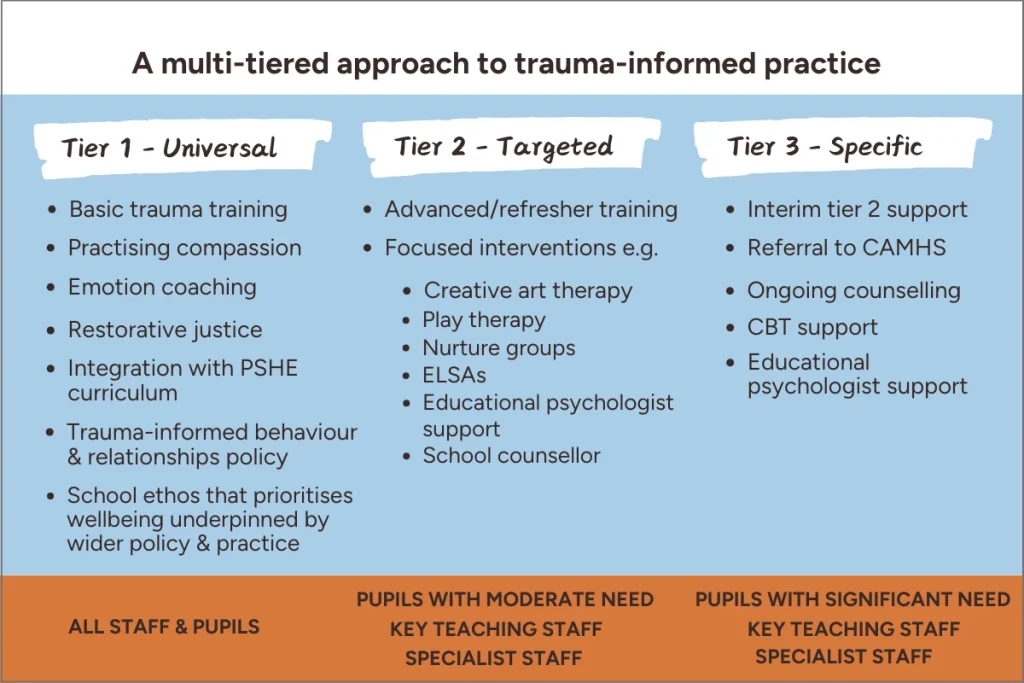

It might be helpful to think about which staff need to be trauma aware (which is potentially everyone, including front-of-house staff) and who in your team might need more advanced or refresher training to develop their practice and become trauma-informed.

Whole-school approach

A whole-school approach is essential to success. One way to think about this is through developing a tiered framework of support, such as the example below.

Consolidating knowledge and reviewing progress

Over time there can be a degree of ‘drift’ away from the original principles of a trauma-informed approach, as defined in your school context. New staff coming into your school may also introduce slight variation based on how things were done in their previous setting. Some of this you may want to embrace, other times gentle course correction is required through regular communications, CPD, role-playing etc.

Why trauma-informed practice should be your ‘North Star’

Children who have experienced difficult life experiences can often become trapped in a cycle of escalation and shame in our schools, with punitive school behavioural management systems making exclusion much more likely.

A trauma-informed approach can support staff with managing pupils’ behaviour alongside maintaining positive relationships and building a sense of safety for all. However, the journey towards becoming trauma-informed as a practitioner and a school seldom travels in a straight line.

Leadership needs to reassure staff that there will be setbacks and it’s important to set aside time for reflective practice so staff can come together to problem-solve and learn from one another. Schools that see the greatest success are those that regard trauma-informed practice as their ‘North Star’, recognising that while there’s no magic reset button, it is a journey worth investing in. Ultimately there can be no sense of ‘belonging for all’ without a better understanding of trauma in schools.

What do you think?