Real Training’s Rosalind Goodwin looks at what makes a strong EHC needs assessment application and how you might be able to streamline the process.

Applications for an EHCNA (Education, Health and Care Needs Assessment) are filling up SENCO “to-do” lists in increasing volume. The number of children with SEND in mainstream schools has risen significantly in recent years; according to DfE statistics, requests for an EHCP increased by a fifth between 2022 and 2023.

As an Educational Psychologist and someone who has sat on many panels where EHCNAs have been considered, I’ve read my fair share of applications. What I’m observing is that an increasing number lack sufficient evidence that the Graduated Approach has been followed, presumably as a result of the sheer volume SENCOs are dealing with. For borderline cases, this can lead to more requests for information from the school, or, in worst case scenarios, decisions not to issue EHCPs that might otherwise have been deemed appropriate.

An EHCP should not be the “de facto” end goal for every child with SEND. The objective of following the Graduated Approach is to properly evidence what progress can be made with planned support in place – rather than setting out from the beginning to document its failure. For quite a few children with SEND a good programme of classroom support alongside help from external professionals will be sufficient – this needs careful communication with parents from the get-go.

But what about those who really do need the EHCNA? Dealing with applications efficiently and effectively is a fine art. There simply aren’t many shortcuts that can (or should) be taken. That said, there may be opportunities to streamline processes without cutting corners, particularly when it comes to making better use of external professionals’ time.

Because this is such an important area, I wanted to briefly outline some ideas and personal observations for improving an EHCNA application and the processes that feed into it.

A thoroughly documented Graduated Approach is essential

It may seem obvious but this is where a large number of requests are falling down. Technically evidence of Assess, Plan, Do, Review (APDR) is not, strictly speaking, required for an assessment. However, its absence would mean that in the majority of cases, it would be very difficult to determine whether an EHCP would be needed. Indeed, it could result in a plan not being issued. (See IPSEA guidance for the regulations around asking for an EHC needs assessment.)

There are three core things I would suggest that will help your application;

- Involve other professionals early and document as you go along, make sure you have a record of how this input has informed your understanding of the child’s needs as well as how you have taken account of any advice provided in terms of support offered to the pupil.

- Show detailed progress, or demonstrate that progress has not been achieved. It might be that a child has made strides, but that the gap between them and their peers continues to widen. This too should be documented.

- Include a summary document in your application, this is incredibly helpful for the reviewer and saves a lot of time.

Take a look at our example Assess, Plan, Do, Review summary template for a hypothetical child with autism that you can download.

Don’t overlook pupil and parent voice

The information you include in your EHCNA application will also be included in the EHCP if the assessment is agreed and an EHCP issued. It is important, therefore, that the EHCNA itself is pupil-centred and reflects authentic collaboration with parent(s) or carer(s).

The SEND Code of Practice outlines this expectation;

- ‘Consideration of whether special educational provision is required should start with the desired outcomes, including the expected progress and attainment and the views and wishes of the pupil and their parents. This should then help determine the support that is needed and whether it can be provided by adapting the school’s core offer or whether something different or additional is required.’ DfE SEND Code of Practice, 2015 – 6.40)

Pupil voice

Aside from the various scales and questionnaires that can be used to capture pupil voice (and specific tools such as Talking Mats for children with more severe needs), there are other creative techniques to consider leveraging. Mind-mapping, for example, can help students work out what they want to say, while using Lego can also be a good route into a conversation. When it comes to self-expression you could use “all about me” videos, or pictures that document how children have expressed their views through art. Transcribe snippets to use within your EHCNA form and refer to images and other multimedia in the appendix.

Explore further: Find out about methods of eliciting pupil voice as part of a person-centred planning approach on our Autism Spectrum Conditions and Advanced SEND Leader courses.

Parental voice

Including parental voice can help clarify aspirations. If they (and their child) really want to remain in a mainstream setting this should be expressed in the application. It is advantageous for an EHCP to contain focused outcomes that are meaningful to the child and their family, rather than so many that it becomes unmanageable and the child can no longer be supported in a mainstream setting.

Consider alternative ways to evidence external professionals’ time

Educational psychologists always wish we could make our allocated time go further. What I want to highlight is that there are different ways of using our time to help understand children’s needs. Bear in mind, if you want to provide ‘proof’ of involvement, it may not be necessary to produce evidence of a full assessment – which could save you valuable EP time. Consultation discussions (which might have been preceded by observation/s) or EP participation in meetings, might be sufficient.

Two important caveats; firstly you must evidence that the outcomes of such discussion have informed the support offered to the pupil. Secondly, variation exists when it comes to each local authority, so it’s important to clarify what expectations exist when it comes to ‘evidence’ of involvement with EHCNA applications.

Also worth considering is whether prior pupil involvement with an EP has been documented in a setting the pupil has recently attended. This may mean that you can use existing EP information to inform the support you are now offering, rather than starting again from square one.

When it comes to working with other supporting professionals e.g. speech and language therapists, specialist teachers etc. similar principles will apply. As ever, things vary according to local authority guidelines, so check expectations about how you evidence the involvement of professionals.

Hold outcomes meetings to avoid overloading an EHCP

In some local authorities, outcome meetings are held once an EHCNA has been completed. However others don’t follow this process, the result being that multiple outcomes are suggested by different professionals completing an EHCNA advice report.

If all of these are included, this might mean that the EHCP has many, (even too many) outcomes – all of which would be expected to be considered during the Annual Review. To avoid this, you might find it helpful to hold a meeting with the child’s parent/s / carer/s together with relevant professionals (Speech & Language Therapist, member/s of outreach teams, EP etc.) before submitting the EHCNA request through which outcomes are agreed.

This means if any professionals are subsequently asked to provide advice, they are aware of outcomes that have been previously consolidated and agreed.

Strong and weak applications for an EHC needs assessment compared

| Strong EHCNA | EHCNA Application with Weaknesses |

|---|---|

Contains evidence of the Graduated Approach having been followed (e.g. several IEPs/ PLPs dating back several months/years are included through which it is clear that earlier IEPs / PLPs have been reviewed. This review clearly informs amendments in targets and provision. There is evidence of authentic engagement with parent/s / carer/s either through their contributions during IEP / PLP meetings having been recorded or inclusion of minutes from other meetings in which they have participated. Contains evidence of involvement of supporting agencies whose input has informed support. | Lacks evidence that the Graduated Approach has been followed. Exceptions might include circumstances such as a child with a very high level of need recently joining the setting where it is clear that their needs will exceed the available provision. |

Contains evidence that supporting agencies have been involved at the appropriate stage and that resultant input and/or advice has informed the support offered. For example, in the EHCNA reports or equivalent form, professional agencies are included. Suggestions regarding support and/or actions agreed during their involvement are referenced in IEPs, PLPs or other documents. In this way it is clear that the Assess, Plan, Do, Review process has been followed. | Includes sections of reports completed by supporting professionals which have been copied and pasted into the EHCNA application. Lacks references to how these have informed an understanding of the child’s needs or the support that has been offered. |

Demonstrates that efforts have been made to capture the voice of the child (format depends upon the age and communication capabilities but might involve approaches such as Talking Mats,) together with the voice of their parent/s / carer/s It is clear that there has been discussion with parent/s / carer/s or that there has been some other format through which they have been invited to share their views and aspirations, e.g., via a MAPs [Making Action Plans] meeting). | There is an absence of the opposite. |

Final thoughts

Having read many EHCNA applications, I have come to recognise how much time and commitment they involve. The dedication of those completing them is evident. However, sometimes applications can just miss the mark in terms of providing depth of evidence that the Graduated Approach has been followed.

It would be contrary to the principles of EHCPs to try and suggest ‘shortcuts’ when completing applications. However, by thinking about how – for the most part – EHCNA requests result from the following of a process through which evidence has been gathered along the way, making the request should (if it’s the right decision for the child) be a meaningful ‘next step’ rather than the start of the journey.

By Rosalind Goodwin – Educational Psychologist

Following work as a primary school teacher, Rosalind (Roz) has been an educational psychologist for over twenty years. She has worked in several London authorities as well as for a range of independent organisations.

Roz has participated in several multi-disciplinary panels including those relating to Education, Health and Care (EHC) Needs Assessments, the issuing of EHC Plans, the placement of children and young people in specialist provisions and panels relating to SEND first-tier tribunal appeals.

New JCQ guidelines have been published

On 28 August, the JCQ (Joint Council for Qualifications) published their 2024-25 regulations and guidance for exam access arrangements.

Real Training’s free online Access Arrangements Update course launched last week and covers everything SENCOs, exam access arrangement assessors and coordinators need to know about the new regulations. This includes walking you through the new forms so that you can approach the 2024-25 exam season with confidence.

Sign up now and benefit from:

- Access to video content from Nick Lait, Head of Examination Services at the JCQ, who takes you through the inspection findings, changes, and answers your questions

- Video reviews of popular tests including the new DASH-2

- Explanation of the role of Access Arrangement Coordinator and an Access Arrangement Coordinator’s guide to working effectively with SENCOs

- Videos demonstrating the completion of:

- Form 8

- Form 8 Roll Forward

- Form 9 for a candidate on a waiting list

- Multiple-choice questions to test your knowledge and understanding

What delegates are saying about this year’s course

“I think the team have excelled themselves again. Fantastic course as always” – Tara McKibben

“As ever, a well-designed and delivered presentation. The notes on the administration of DASH-2 were a useful reminder. Thank you.” – Candy Clarkson

“Excellent course much more practical than previous years. Good case studies and practice forms will be helpful to use as good practice examples. Q&A helped to clarify and re visit the changes. Tests and multiple choice questions are a great refresher.” – Mary Agnew

“Thank you for a very useful and informative course. I am overjoyed you offer this every year free of cost. It is hugely appreciated.” – Annabella MacLaren

Have you thought about hiring an access arrangements coordinator?

Would you like some help with the administrative elements of access arrangements? When asked about the benefits of having an access arrangements coordinator, Nick Lait from the JCQ had the following to say:

“Trying to juggle senior leader responsibilities as well as exam access arrangements as a SENCO is very difficult. Having an Access Arrangements Coordinator in place can pay real dividends.

Training is desirable as it equips that person to make decisions independently or defer to the SENCO where required and, of course, ensures they have a thorough understanding of the latest JCQ regulations.”

Nick Lait – Head of Examination Services – JCQ

New course for Access Arrangements Coordinators launching 20 September

Our new course – coming soon on 20 September 2024 – is designed specifically for Access Arrangements Coordinators. It includes training on the latest 2024/25 JCQ guidelines, and will teach Coordinators the knowledge and skills they need to become a member of the team that ensures students receive the reasonable adjustments they need for success in exams.

For more information about the role of Coordinator, and details about the course, visit our dedicated Access Arrangement Coordination course page.

We have been shortlisted for a Teach Secondary Award!

We are delighted to announce that our Safeguarding AI course has been shortlisted for the School Business and Procurement category in the 2024 Teach Secondary Awards!

We’re thrilled that our new course, developed in partnership with Educate Ventures Research, have been recognised, alongside our commitment to equip schools with the knowledge and tools required to implement AI safely and responsibly.

The results will be announced in November.

About our Safeguarding AI course

Our Safeguarding AI for Leaders (SAIL) course is designed for Designated Safeguarding Leads (DSL) or other leaders in your setting with responsibility for safeguarding, pastoral care and/or technology implementation and use. This comprehensive course equips participants to develop and implement robust AI safeguarding policies, procedures, and action plans. Through a blend of expert guidance, practical tools, and peer networking, participants will gain the confidence and knowledge to lead on safe and ethical AI use in your setting. With a duration of 4-5 hours and 12 months of ongoing support, SAIL offers exceptional value and flexibility.

Announcing our partnership with Teach First

We are pleased to announce that, working in partnership with Teach First, we will be delivering the new NPQ SENCO.

NPQs are the most widely recognised qualifications in the education sector for current and aspiring leaders. This new NPQ for SENCOs will be the mandatory qualification for anyone who wishes to qualify and work as a SENCO in state schools, from 1 September 2024.

Having trained over thousands of SENCOs, being able to offer the new NPQ is an exciting next step in our mission to provide education professionals with high quality training that allows them to support the needs of students in their school or setting.

We have chosen to partner with Teach First as our values of making education accessible for all and developing high quality teachers align. Teach First have an established track record in leadership development, and have been an accredited NPQ provider for several years with excellent feedback from participants.

We are involved in the curriculum design process and our team of course facilitators support the programme delivery.

Our NPQ SENCO course offers a blended learning approach, comprising flexible online learning, engaging seminars and thought-provoking in-person conferences, all led by experienced facilitators who have worked within the sector and our team of Educational Psychologists. You can look forward to learning at your own pace and from anywhere, while collaborating and sharing best practice with a network of SENCOs and SEND experts.

We are now accepting applications. The deadline for the first cohort is 17 September 2024, with the course starting in October 2024. We advise applicants to apply as soon as possible in order to guarantee a space.

To find out more about our new NPQ SENCO, visit the course page here.

Emotional intelligence is more than naming feelings, it is a person’s overall ability to deal with their emotions….

There are five main aspects of emotional intelligence which, when developed, lead to children becoming emotionally literate. These are:

- Knowing emotions – A child recognises a feeling as it happens.

- Managing emotions – A child has ways of reassuring themselves when they feel anxious or upset.

- Self-Motivation – A child is in charge of their emotions, rather than controlled by them.

- Empathy – A child is aware of what another person is feeling.

- Handling relationships – A child is able to build relationships with others.

Encouraging young people to understand the difference between “sad”, “disappointed” and “upset” acts as springboard to develop appropriate strategies. Every emotion word learnt is a new tool for future emotional intelligence.

This resource helps children to identify and articulate their emotions and start to discuss and understand how they are feeling.

For more information about our courses on emotional regulation take a look at our Social and Emotional Mental Health course or our short CPD from our sister company, Dyslexia Action, on the Emotionally Connected Classroom.

This year we had a record-breaking number of delegates graduate with a postgraduate award. We were excited to have the opportunity to celebrate with some of them at their Middlesex Graduation ceremony!

Delegates achieving a Postgraduate Certificate, Postgraduate Diploma, or Master of Education were invited to don their cap and gown at the recent Middlesex University graduation ceremony and we were delighted that so many were able to attend in-person.

The graduation event is more than just a ceremony for our graduates, it’s a chance to celebrate their hard work and connect with their peers. Just before the ceremony, we raised a glass to our graduates’ success at a drinks reception, which was a fantastic opportunity for graduates, their families, and our team to mingle, share stories, and celebrate all that has been achieved.

We also took the opportunity to set up a filming booth to capture our delegates’ experience of studying with Real Training and find out about the positive impact their training has enabled them to have in their setting. It has been such an honour to be part of each of our delegate’s learning journeys, and we can’t wait to see where their new qualifications take them.

So, a massive congratulations to all of this year’s graduates and to those delegates currently studying with us, we hope to be able to celebrate with you in the future!

Feeling inspired? Why not take a look at our courses to see how you could further your career.

This resource is designed to help develop pupils’ spatial thinking and non-verbal reasoning skills through a series of tasks that require them to closely examine patterns. It has been designed in PowerPoint to make it easy for you to edit and add your own notes for learners. Many of the shapes are editable to allow teachers to create further patterns.

Explanatory notes and answers can be found in the accompanying download.

Don’t miss Gill Cochrane’s article: Making maths stick: The Importance of Spatial Thinking. Gill explores the latest thinking on spatial thinking and relational reasoning and how teachers can help build these skills in order to protect against later maths difficulties.

Encouraging more spatial thinking in maths can have a big impact on children’s confidence and overall ability. Gill Cochrane explains the close link between spatial thinking and reasoning skills and outlines some practical things teachers can do to help. [Don’t miss our free resource at the end].

Whilst teaching maths as a primary school teacher, I became fascinated with the idea of ‘semantic glue’ – or what makes information ‘stick’ in our memory. The pursuit of answers to ‘the glue question’ led me to undertake a psychology degree. During my studies, I came across these words from the Nobel prize-winning scientist Eric Kandel:

“Memory is everything.

Without it we are nothing.“

– Eric Kandel

Kandel studied Californian sea slugs to reveal how memories are formed. This research helped demonstrate how memory supports the process of monitoring for safety when we are moving through space. Human functioning and reasoning essentially evolved to serve this need. Grasping this powerful idea allows us to appreciate how inextricably linked spatial processing and reasoning are.

There are three essential steps in both processes:

- adding new information to what you already know and hold in memory

- relating and connecting this information to what’s already known

- using this new information to achieve a purpose or find solutions to challenging situations.

Essentially, both boil down to extracting meaningful patterns from the environment. Understanding this helps to explain why the latest research into how children learn maths has demonstrated a causal relationship between spatial thinking and academic outcomes, prompting increasing calls to spatialise the maths curriculum. It could also explain why weak verbal and spatial working memory are commonly associated with maths difficulties and maths anxiety.

So how can we, as teachers, exploit the connection between reasoning and spatial skills to help re-address difficulties with maths learning?

Pattern detection and relational reasoning skills

Relational reasoning makes a unique and positive contribution to maths outcomes. Giving pupils early and explicit experience in rule-following will improve their ability to monitor sets of information for patterns.

Attribute blocks vary in shape, thickness, colour and size; early sorting work with these blocks encourages learners to observe and describe relative differences and similarities and boosts maths vocabulary. Venn diagrams give a great framework for further explicit categorisation work using the blocks. Children can then build on the knowledge gained sorting shapes to generate patterns. This is an important skill, as it involves the application and creation of rules.

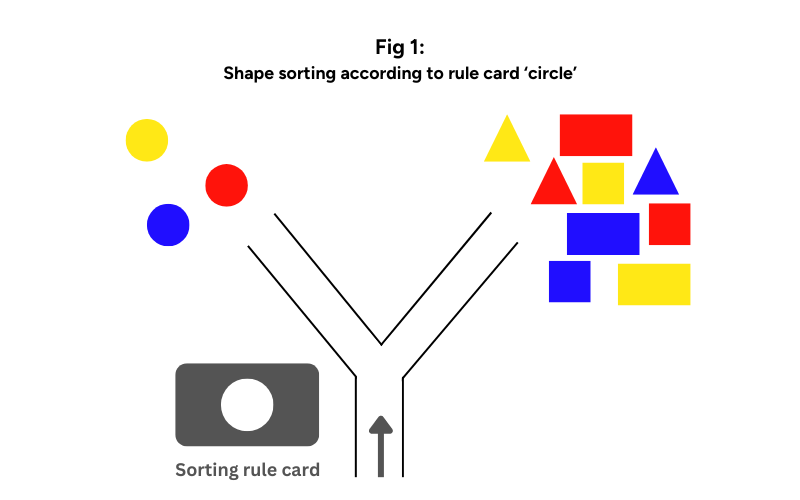

Activity 1 – Sort it out: Present children with an assortment of attribute blocks and a simple rule card that says, for example, ‘circle’. Ask them to sort shapes according to the rule. Gradually make this more complex by adding more than one rule for example, ‘circle’ and ‘thick’. You can see this in Figure 1.

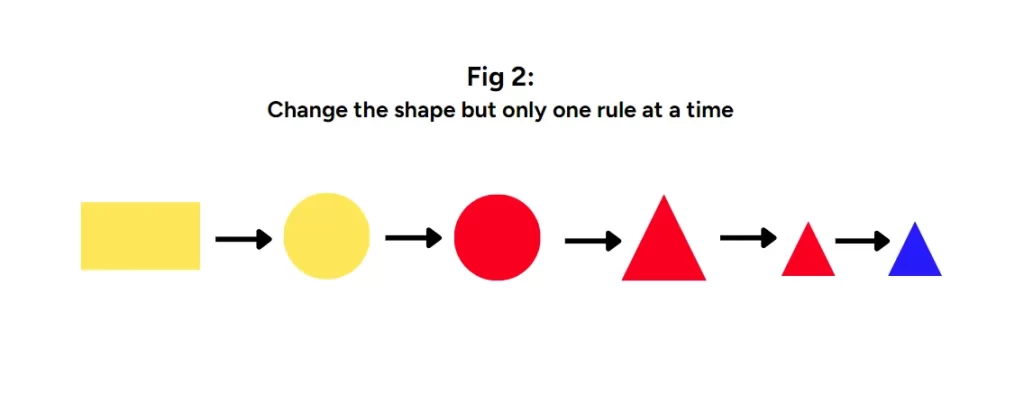

Activity 2 – One at a time: Give pupils a set of attribute blocks each and ask them to play a domino game where the rule ‘only one change at a time’ governs the flow of play. They will need to take turns to put down blocks between them, but they won’t always be able to go. An example sequence from a game is shown in Figure 2 below.

For progression, you could also ask pupils to work together or independently to determine the steps they must go through in order to get from an initial state to an end state in the shortest number of moves by changing only one attribute at a time. For example, ‘How many steps does it take to get from a large, red, thick circle, to a small, blue, thin triangle?’

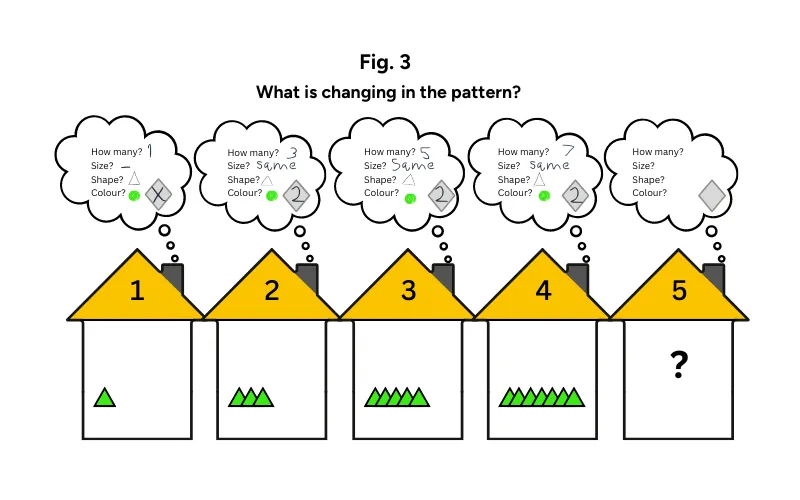

Activity 3 – Patterns: You can encourage children to discuss their reasoning by providing prompts to structure their analysis of a pattern. In Figure 3 you can see how pupils are asked to fill in information about every stage of a pattern. For example, has the number of objects changed? Are they the same shape? The grey ‘difference diamonds’ featured in the speech bubbles prompt the recording of this crucial bit of between-item information. Providing the numerical term positions on the roofs helps to structure discussion of the pattern and predictions of the next item in the series. Developing pattern detection skills like this will help children move on to more complex non-verbal reasoning.

Analogical reasoning

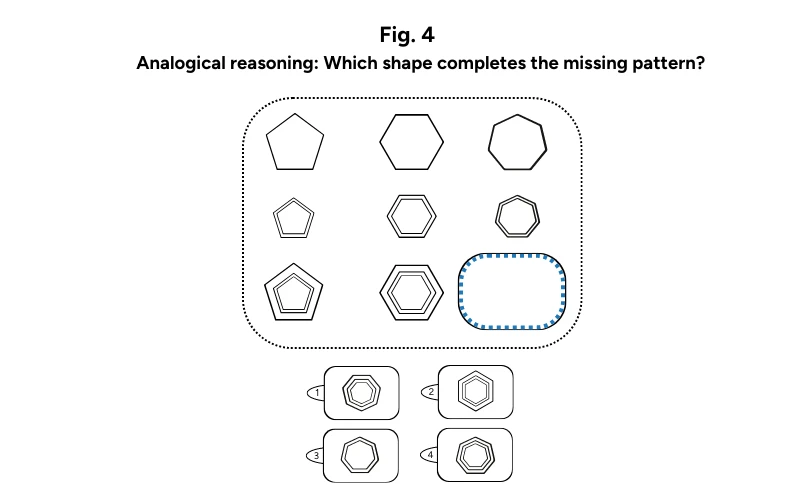

This is perhaps the most familiar type of reasoning, and it features in many popular matrix tasks, such as Figure 4. In activities like this, the learner needs to choose the right shape to complete a pattern. Information can be deduced by looking at the relationships between the two other given sequences; potential answers are displayed immediately below each question.

It’s important for us, as teachers, to understand the steps in the exploration that lead to the solution.

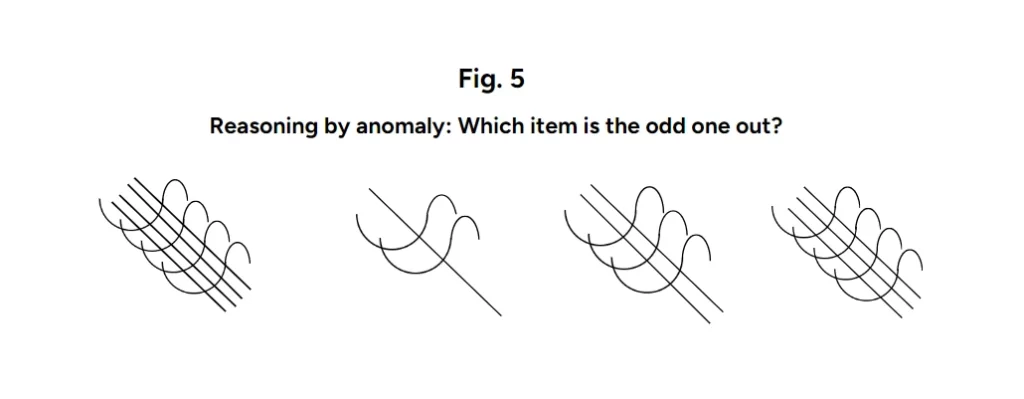

Reasoning by anomaly

This involves working out the rule behind various patterns and then spotting the sequence that isn’t following it. Look at Figure 5. By studying each of the patterns and the interrelations within them you will start to appreciate how practice in this type of task promotes structured scrutiny of the relationships within and across the set items.

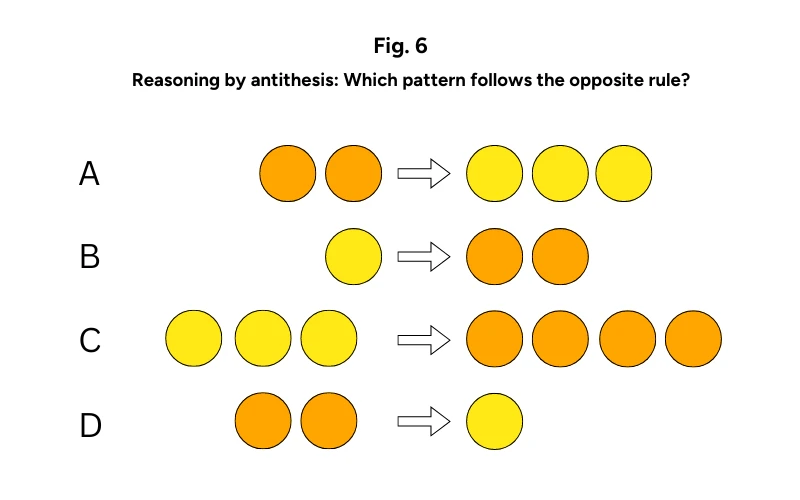

Reasoning by antithesis

This requires learners to identify when a parallel or opposite rule has been applied. This is more complex, as the process must be identified so the sub- item featuring the opposite process can be chosen. Practice with all these types of non-verbal reasoning tasks is done without processing number systems, allowing analytical skills to be strengthened separately from numeric work.

There is evidence that this type of reasoning practice can help when it comes to work with numbers.

Purposeful scanning

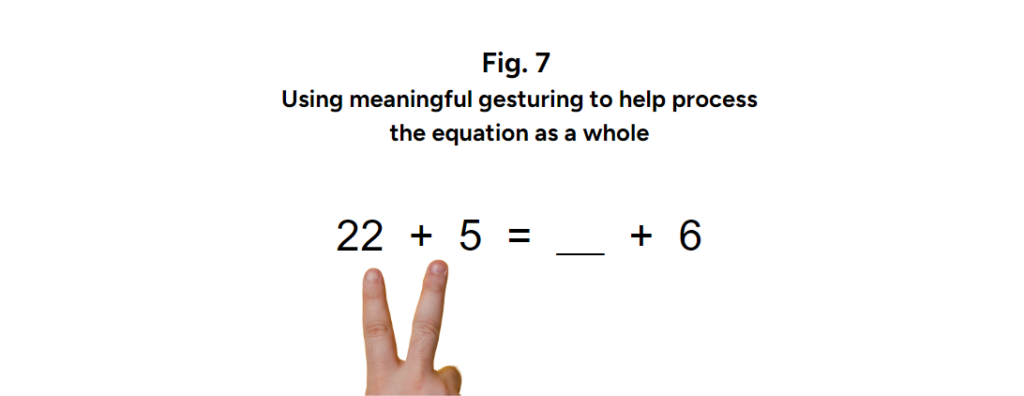

A rich body of research demonstrates that purposeful scanning of information can significantly aid the ability to solve problems. There are indications that providing practice in explicitly noticing relationships within written equations can boost performance on similar maths problems. For example, building meaningful gesturing into the appraisal of sums can lead to better performance on tasks involving the equivalence concept.

Ask pupils to use their index and middle fingers to touch each number before the equals sign (and any after it) and then to use their index finger to point to the missing information. (See Figure 7). The gesturing enhances the processing of the equation as a whole, working from left to right.

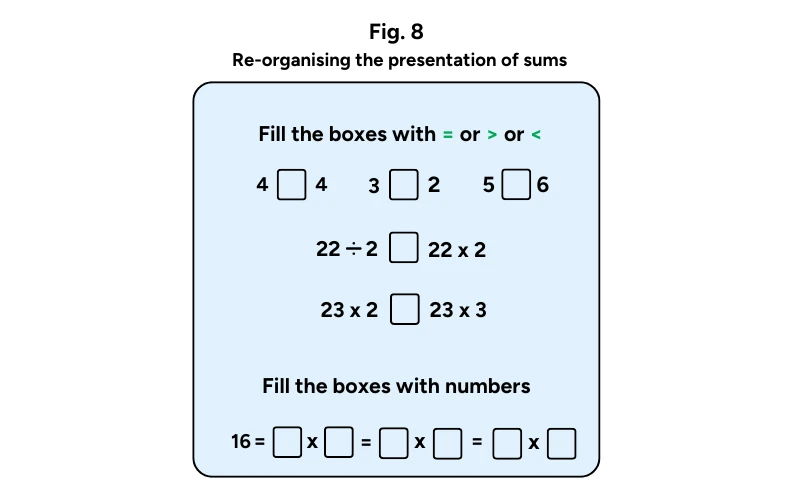

Changing how we present sums can alter the way pupils monitor the equations set and boost performance. Re-organising the presentation of a problem (see Figure 8), promotes scanning of the whole sum, and examination of the interrelationships within it.

In time, with supporting, structured discussion, learners can develop flexibility in strategy use when calculating, which can reduce the need to calculate in some cases. The children will learn to exploit the inter-relations to reduce the cognitive load of computation.

Read also: Understanding maths difficulties

Organising numbers and fractions spatially

Recent research has shown that lower levels of maths anxiety are found in people who ‘spatialise’, organising sequences from left to right in verbal working memory.

Here are some ways we can help children spatialise their mathematical understanding:

- Number lines and bar models should be modelled as important organisers of computational thought.

- Work on fractions should include their ordering on number lines to make relative value explicit.

- Cross-sectional drawing can provide an additional way to map space to solve word problems.

There is a causal link between spatial thinking and achievement and confidence in maths. Spatialising maths builds an appreciation of the relations between and within objects and ultimately contributes to a more secure mathematical understanding in the longer term.

Gill Cochrane is a former primary school teacher. She is now the lead developer on the specialist literacy and maths courses run by Real Training in partnership with Dyslexia Action.

Find out more by visiting realtraining.co.uk/maths-courses

Free resource!

| Gill’s Top Tips for Building Maths Confidence |

| Reduce reliance on memorisation for learning basic number facts; use number relationships and reasoning strategies instead. Try conceptual instruction using a limited range of numbers (e.g., 1 to 9), their sums and associated subtraction facts. This makes it easier to analyse the relationships between the elements within the sums. Use exploratory work on factor pairs to help encourage more flexible calculation strategies. Giant number lines can help young learners to walk through sums and to conceptualise counting as ‘moving on.’ Gesture and personification have been shown to increase retention and deepen understanding by recruiting a wider range of memory systems. Use concrete resources for teaching angles for example, using hinged strips to show that an angle is a measurement of turn. Promoting maths oracy should be an important feature of each maths lesson. |

We are excited to announce we have launched a brand new course, aimed at ensuring the safe and ethical integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in education.

Our Safeguarding AI for Leaders (SAIL) course is tailored for Designated Safeguarding Leads (DSLs) and school leaders, focusing on developing and implementing robust AI policies within educational settings. Developed in partnership with AI experts Educate Ventures Research (EVR), it is designed to equip educators and school staff with the knowledge and tools needed to navigate the evolving landscape of AI while prioritising student safety.

The new course addresses key areas such as:

- Adapting safeguarding practices for AI

- Exploring new threats and ethical considerations

- Ensuring security and compliance with regulations, practical implementation strategies.

It has been a please to develop this course alongside Educate Ventures Research (EVR), leaders in the field and who have brought their expert knowledge, evidence-based strategies, and practical guidance to the programme, enabling delegates to learn how to responsibly integrate AI into educational practices.

For more information, including eligibility, start dates, costs, and duration, please visit the Safeguarding AI course page here.