Comprehensive training course for new or aspiring Assistant SENCOs

We are delighted to announce the launch of a new apprenticeship programme, designed to equip new or aspiring Assistant SENCOs with the essential knowledge and skills to support effective provision for pupils with special educational needs.

As the first apprenticeship specifically created for Assistant SENCOs, participants will explore national policies and legislation, learn how to align the school’s SEND vision with broader improvement plans and gain the skills to implement effective projects, delivering meaningful and sustainable change for pupils with SEND.

The 15-month programme, delivered through a blend of asynchronous study, live online workshops and project work, will enable Assistant SENCOs to support their SENCO in making data-driven decisions, including monitoring and evaluating interventions for pupils with SEND. They will also learn to collaborate effectively with their SENCO, teachers, support staff, parents, and external agencies to document progress and ensure the individual needs of pupils are effectively met.

Participants will enhance their team management skills, including coaching and mentoring, conflict resolution, and effective strategies for communication, collaboration, and problem-solving.

SEND experts from Real Training have co-designed the programme, with our Ofsted ‘Outstanding’ sister company, Educational and Sporting Futures (ESF). Schools can use the Apprenticeship Levy to fund the training and upon completion, participants will receive a Level 5 Operations Manager Apprenticeship.

Find out more and apply

To find out more, including eligibility requirements, please visit our course page.

The first cohort begins on 11 June 2025 and we’re accepting applications via our online registration form.

Growing portfolio of SEND focused apprenticeships

The Assistant SENCO programme is the latest in our suite of SEND-focused apprenticeships. The Real Training team also works with Educational and Sporting Futures on:

- Level 3 Teaching Assistant Apprenticeship with SEND focus

- Level 5 Specialist Teaching Assistant Apprenticeship (with a choice of SEND, Literacy or Social, Emotional Wellbeing specialism)

- Level 7 Advanced SEND Leader Programme

We’d all like to think we are good listeners but how often do we listen to reply rather than listening with genuine empathy?

This resource breaks down the skill of active listening and explains some of the key things that good listeners tend to do (and what they avoid!).

Includes: Active listening worksheet for teens as well as four activity ideas for PSHE lessons. Take a look at our accompanying blog.

As an SEN or Inclusion professional based internationally, you’ve likely heard about our popular iSENCO course and also the new UK qualification; the NPQ SENCO.

How do you know which course to choose? It’s worth reflecting on the immediate needs within your setting, your personal goals and the different course objectives.

You may not be aware, for example, that the iSENCO (International Award in SEN Coordination) has been designed specifically for current and aspiring SEND leaders based in international settings. Tutoring is provided by SENCOs or other senior leaders responsible for inclusion in international schools and there will be chances to share ideas and best practice with international colleagues. Successful completion leads to a Middlesex University Post Graduate Certificate (one third of a MEd).

Below are a few helpful pointers to help you decide which course is right for you – bear in mind that you may even wish to study both at some point.

NPQ SENCO at a glance

The NPQ SENCO is the current qualification that all SENCOs based in England need to complete within three years of taking the post. It covers all you need to know about the operational, practical and legal aspects of being a SENCO – specifically in a UK school environment.

Pros:

- Qualifies you to work as a SENCO in state schools in England, should you wish to return. However, it’s worth pointing out that Wales and Scotland operate under different systems and the qualification is not a Government-mandated requirement for working in independent schools.

- A widely recognised qualification. Although we’re not currently in a position to offer international delegates the option of completing the NPQ SENCO, if you choose to study elsewhere, you can still bring in 30 credits towards any of our postgraduate programmes, as recognition of prior learning.

Things to consider:

- Some course content is focused purely on understanding legislation in England which is unlikely to apply to your international setting.

- More of an emphasis on SEND management/operational leadership rather than strategic leadership and refining leadership skills.

- Requires some ‘live’ online delivery – potentially at some very unsociable hours(!) for SENCOs based in different parts of the globe.

- Requires 18 months of study, plus a 3-month window for completing the final case-study assignment meaning a greater time commitment, compared to the 12-month iSENCO.

- Places can be limited because of the in-person requirement. It is also planned that start dates will only be in September.

- Places can be limited. English SENCOs are prioritised and it is planned that start dates will only be in September.

iSENCO – International Award in SEN Coordination

The iSENCO is primarily designed for SENCOs and aspiring SEND leaders but it’s highly relevant to anyone who holds a key inclusion role in an international setting. This rigorous programme offers a rich learning experience with a blend of practical tasks, theory, reflection and project-based assignments. There is an emphasis on developing leadership skills to set you up for success.

Every year it attracts a diverse range of professionals who lead on SEND and inclusion (including SENCOs, Inclusion Managers and Inclusion Heads), as well as teachers and experienced teaching assistants who want to deepen their expertise or eventually move up to a leadership position.

Pros:

- Specifically designed for international schools, with expert tutors (many of whom are current or former SENCOs or inclusion leaders in world-renowned international institutions).

- Course material tailored to SEND and inclusion in an international context. For example, you will learn how to;

-

- Differentiate between pupils who may have English as an additional language and/or SEND

- Lead with confidence within an international context

- Collaborate effectively with colleagues and manage and develop staff within a multicultural context

- Work with parents and local teachers who may hold different cultural attitudes towards SEND

- Manage SEND provision where teaching assistant expertise may be less extensive than in the UK and support from external professionals harder to come by

- Review and understand cultural identities, including challenges often felt by Third Culture Kids

- Comprehensive leadership training for SEND and Inclusion roles. Develop the skills to influence the strategic vision for inclusive education, as well as reflecting on your own strengths and weaknesses using a leadership behavioural assessment tool.

- Evaluate SEND provision in a different setting. Delegates particularly enjoy the opportunity to complete a project where they visit a different setting and reflect on their approach to SEND and Inclusion. Our online network helps you connect with fellow SENCOs to secure a placement.

- Designed for self-paced online study. Going online means more flexibility – entirely removing the hassle of arranging cover during school hours.

- Build a peer network. As part of your study, you will be encouraged to join one of our communities of learning to share your reflections and contribute to discussion groups.

- Carry out projects that make an impact. During the course, you will critically review SEND policy, data management, and provision within your setting, identifying and making improvements. You will also either design and carry out a project to support the assessment or provision of services for pupils with SEND, or write a case study on an intervention conducted with an individual learner. Previous projects have included everything from the use of Lego therapy to Nessy Reading and Spelling interventions.

- Standalone course or credits towards a masters. Can be taken as a standalone level 7 Postgraduate Certificate, equivalent to 60 credits. Or take the credits and use them as part of any of our postgraduate programmes, including our Masters in SEND and Inclusion, Masters in Mental Health and Wellbeing in Schools and Colleges, Masters in Inclusive Educational Leadership or Masters in Educational Assessment.

Things to consider:

- A more strategic, premium course that comes with slightly greater financial commitment.

- More in-depth, comprehensive training that may not suit everyone – but if you want to make more of a transformative impact, it will set you up to do so. Find out more about the course here.

- Three starting points each year; January, May and September.

Which schools have iSENCO delegates come from?

We’ve supported delegates training across more than 44 countries and from international and community based settings. Just a few include;

| School name | |

| Sherborne School, Qatar Brighton College, Abu Dhabi Alice Smith School, Kuala Lumpur Campion School Tanglin Trust School The British School in Tokyo Champion School, Athens British School Muscat Doha College Repton Schools Dulwich College, Beijing Safa Community School | Aiglon College International School of Geneva La Garenne International School Lyceum Alpinum Zuoz Bangkok Patana School American School Grenoble North London Collegiate School Jeju Mougins School The English School Nexus International School, Singapore Hillcrest International School, Kenya Cambridge House Community College |

What do previous delegates say about the iSENCO?

“The course has empowered me to implement targeted interventions that have already shown remarkable results. The assignment comparing SEND policies and settings between two schools turned out to be particularly impactful. By examining different approaches, I identified key areas for improvement and implemented strategies that fostered a more inclusive environment.

Would highly recommend to other SENCOs based abroad.”Amna Shahid – Pakistan

Incredibly transformative! This course has enabled me to become an effective SENCO empowering those who I lead. I have completely rethought how information is shared with parents, had the opportunity to implement an impactful intervention and learned more about myself as a leader.

Pearl Demosthenous – UAE

“I strongly encourage anyone considering broadening their understanding of inclusion within an international context to take this course. It attracts inclusion teachers from all over the world, making it a valuable and diverse learning experience. This course holds significant recognition in the Middle East region, particularly in Dubai. This accreditation can greatly bolster individuals seeking a SENCO role in this area.

Pavla Pilbauerova – UAE

“Very beneficial for my professional progression and personal growth! Would very much recommend.”

Jessica Follett – Hong Kong

“Definitely worth your time, attention and money”

Petrus Vreugdenburg – UAE

“I have really enjoyed the course…[..] the access it gives to people to be able to communicate worldwide is really useful. It is an important topic that requires an understanding of what others are doing, what works for them and any resources useful to other schools.”

Sophie Kilding – UAE

“A great course; well organised and content-rich compared to other courses my SENCO contacts have been on.”

Jane Barthelay – France

“It is amazing – I find myself being consulted by my school leadership team for SEN policies, student-related issues, admissions and provisions even though I’m not the SENCO. Parents, teachers and students all co-operate in their own way to make their role and mine and success. I feel like I have earned their trust and this is very important for me. I am so proud of my iSENCO!”

Ranjana Ranganathan Ramanathan – Qatar

“This course is great value for money for overseas teachers and well structured.”

Elizabeth Mayou – Luxembourg

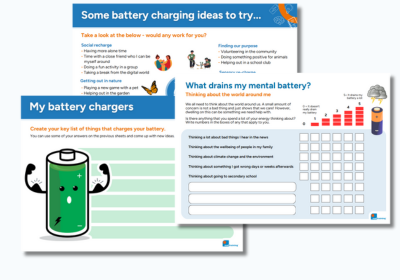

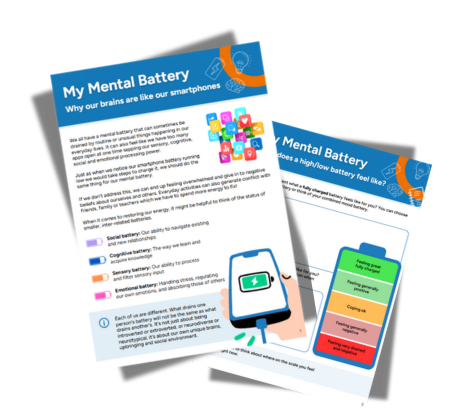

These mental health resources are designed to introduce children to the concept of their personal emotional battery and encourage them to reflect on what drains and recharges it. The aim is to help build resilience and a set of personal strategies to help them plan ahead and manage day-to-day stressors.

Charging My Mental Battery:

KS2 Primary Resource

We all have things in our lives that absorb a lot of our mental energy. Our brains need recharging sometimes – just like a battery does.

This resource looks at some of the things most likely to be impacting children in Year 5 and 6, helping them build self-awareness and develop personal recharging strategies to improve their mental wellbeing.

Includes: Worksheets, activities and a battery-charging weekly planner.

Charging My Mental Battery:

Resource for Teens

This resource helps teens build awareness of things that drain their emotional, social, cognitive and sensory battery.

It provides tips for managing stress as well as encouraging teens to think about different strategies to restore their mental and emotional energy. It also includes a basic energy accounting tracker which neurodiverse students might find especially helpful.

Includes: Teacher guidance notes, worksheets, battery charging weekly planner and energy accounting tracker.

After beginning her career as a Graphic Designer, Amna transitioned to supporting students with diverse learning needs at a British school in Dubai and is now the Inclusion Lead at an IB school in Pakistan and SENCO for students in Middle Years and Diploma programmes.

Committed to professional development, Amna says she “embraces the belief that education is a lifelong process,” something she passionately believes is “particularly crucial in the field of inclusive and special education.”

How has the course helped make an impact at school?

Initially unable to pursue an on-campus MEd, I chose Real Training for its online flexibility and tailored module selection. This allowed me to focus on areas like iSENCO, aligning perfectly with my interest in inclusive education.

What made you choose the Real Training course over other options?

The iSENCO course has directly improved the learning outcomes of students in my setting by enabling more effective and inclusive educational practices.

I have successfully enhanced and refined SEND policies leading to noticeable academic and social performance improvements and a forthcoming data management system is poised to better track and support individual student needs. The course has also empowered me to implement targeted interventions that have already shown remarkable results.

The assignment comparing SEND policies and settings between two schools turned out to be particularly impactful. By examining different approaches, I identified key areas for improvement and implemented strategies that fostered a more inclusive environment. This task encouraged a critical evaluation of existing policies and inspired innovative thinking in tailoring our approaches to meet diverse learner needs effectively.

I’ve also improved the strategic use and budgeting of SEN resources and I’ve enhanced the professional development of Learning Support Assistants (LSAs) through targeted training and coaching.

How has the course helped you develop professionally?

Participating in leadership and SEN-related workshops has prioritised my personal and professional growth, enhancing my ability to lead and advocate for effective SEND provisions. Moreover, I’ve increased interactions and collaborations with parents and external partners, strengthening the support network for our students and fostering a cohesive community focused on inclusive education.

Overall, the iSENCO course has been invaluable in equipping me with the tools to enhance SEND provision in my professional setting, benefiting the learners we aim to support. I would highly recommend it to other SENCOs based abroad.

What did you enjoy the most about the course?

I enjoyed the practical application of the concepts learned, particularly the assignments that allowed me to directly improve my school’s SEND policies and practices. The opportunity to engage deeply with specific issues, such as comparing SEND policies between schools and implementing a data management system, was especially rewarding. These tasks enhanced my professional skills and had a tangible impact on my educational setting, making them the most enjoyable and fulfilling aspects of the course.

What are the top three things you have implemented since or during your study?

- Expanding on the success of my case study intervention I’ll be planning further personalised learning strategies to meet diverse student needs.

- Establishing a robust data system will enable more precise tracking of individual student progress and the effectiveness of different interventions.

- Organising and possibly leading training sessions for staff on the latest SEND strategies and interventions can also improve the overall effectiveness of my school’s SEND provision.

Neurodiversity Week 2025 is just around the corner….

Neurodiversity Celebration Week was started by Siena Castellon, an autistic teenager who also has ADHD, dyslexia, and dyspraxia. This year (March 17th- 23rd) will be the seventh annual Neurodiversity Celebration Week since it began in 2018!

Siena started the awareness week with the aim of challenging stereotypes and misconceptions about neurological differences, promote inclusive environments and recognise the many talents of neurodivergent individuals.

To celebrate, we’ve produced some Neurodiversity Celebration Week colouring posters which are great for young people of a variety of ages and can be used as part of wall displays or mindfulness clubs.

8 Ideas for Celebrating Neurodiversity Week in Primary and Secondary Schools

- Student entrepreneur fair or rainbow cupcake sale – host a lunchtime event and raise money for a charity championing neurodiversity.

- Facts and myths board – divide a display board into a ‘facts’ and ‘myth’ section about ADHD, autism, dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia, Tourette’s (or any other form of neurodivergence) and ask pupils to pin statements on either side to create a display.

- Build your own character strengths profile – VIA Institute on Character is a non-profit organisation offering a free online tool that allows students to uncover their strengths. Students could use the report generated to make a poster illustrating their attributes and also think about what helps them to learn. Suitable for ages 8 – 17 https://www.viacharacter.org

- Neurodivergent guest speakers – invite people in the local community to host a workshop or present an assembly.

- Video messages of support – suggest to your neurodivergent pupil alumni that they might like to send in video or voice messages of support to current students. Current neurodivergent older students (or school staff) may also like to send in their messages for younger pupils.

- Dress in rainbow colours, wear something sparkly or wear footwear of their choice to represent how we all think differently and all minds deserve to shine.

- Book club – choose a class book to read that has a neurodivergent main character e.g. Percy Jackson and The Lightning Thief.

- Origami umbrellas – students can follow the video below to create their own. You could ask them to also write down one stereotype about neurodiversity to avoid making. Create a wall display with the results. Watch the video here. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hp9Zn89xG_Y

Don’t forget to take a look at the fantastic resources on the Neurodiversity Celebration Week website.

What are the most commonly used symbols for neurodiversity?

- The infinity symbol represents the infinite variations of neurocognitive functioning. The rainbow colours signify the diversity of the neurodivergent community.

- Umbrellas represent the fact that “neurodiversity” is an umbrella term for a wide range of neurological differences.

You may see a puzzle piece symbol being displayed – particularly to represent autism. However, many autistic people prefer this not to be used as it implies people are a problem to be fixed.

What are the most commonly used symbols for neurodivergent differences?

- Autism – a rainbow infinity symbol, ribbon or colour blue

- ADHD – a butterfly

- Dyslexia – the letters “p” “q” “b” and “d” together

- Dyspraxia, Tourette’s, DLD, dyscalculia and other conditions – don’t have officially recognised symbols, but the sunflower motif represents hidden disabilities and a rainbow infinity symbol is often used. Some people also use teal ribbons.

Introducing: Practitioner of The Dyslexia Guild – Assessor of Access Arrangements

We’ve been working alongside our sister company, The Dyslexia Guild, to create a new membership grade for Certificate of Psychometric Testing, Assessment and Access Arrangements (CPT3A) graduates.

Recently launched, the Practitioner of The Dyslexia Guild Assessor of Access Arrangements (PDG3A) membership, provides a number of professional benefits to those who have studied our CPT3A qualification. By choosing to become a member, you’ll be able to:

- Gain formal recognition for your expertise in access arrangements assessment

- Connect with a network of like-minded professionals dedicated to supporting individuals with dyslexia or literacy-related difficulties and those that require access arrangements

- Borrow selected assessment tests for free through our library*

- Participate in a variety of opportunities for professional development

- Save up to 10% off most products purchased through the Dyslexia Action Shop

- Enhance your professional standing and demonstrate your commitment to best practices.

*terms may apply

Eligibility

To be eligible for this grade of membership, you must hold the Certificate in Psychometric Testing, Assessment and Access Arrangements (CPT3A) from Real Training (similar courses will not be recognised).

Please note: this grade is not applicable for those who already hold Guild membership at Member (MDG), Fellow (FDG) level or those who already have an Assessment Practising Certificate (APC).

Feedback from our delegates is very important to us. This is why we ask every delegate to fill out a feedback form upon completion of their course. This provides us with extremely valuable data on what we’re doing right, and where we can improve.

We’ve been carefully analysing the data from 2024, and below are highlights from the results.

- 93% of delegates rated our course as ‘good’ or ‘very good’.

- 94% of delegates rated the extent to which their course met their developmental priorities as ‘good’ or ‘very good’.

- 94% of delegates rated the course tutor feedback, support and interaction as ‘good’ or very ‘good’.

Comments from our delegates!

“I have found the feedback extremely informative and it has helped to develop my academic writing. My tutor was quick to respond to emails and answer any questions I had”

- Samantha Hutton, Autism Spectrum Conditions delegate, 2024

“The in-person work was inspirational. It was really clear and useful. Feedback on all aspects of the course throughout the online section has been really constructive”

- Mark Westwood, CCET Intensive delegate, 2024

“I felt well supported, any queries were answered straight away and I always felt like I was talking to a real, knowledgeable person rather than getting a standard response”

- Victoria Rogers, Dyslexia Professional Report Writing delegate, 2024

“My tutor was always responding to my questions and provided excellent feedback on the improvement of my essays”

- Panagiota-Maria Pantoulia, International Award for SEN Coordination delegate, 2024

“The tutoring I received was excellent, really useful suggestions and advice and any questions that I asked were responded to promptly”

- Jo Platt, Senior Mental Health Leadership Certificate delegate, 2024

If you are thinking of enrolling on a course with us, either for the first time or are a returning delegate, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us on +44 (0)1273 35 80 80 or contact us here.

We all like to think of ourselves as good listeners. Especially those of us who work in education. But the ability to listen actively is a distinct skill that’s not as intuitive as it first appears.

When we hear about a problem or challenging situation being articulated by a colleague or young person, our instinctive response is to try to analyse that problem and help them fix it. But in some contexts, this natural desire to problem solve and to make the person feel better as soon as possible, needs to be put on ice.

We have to slow down and just be in the moment with the young person, absorbing and sitting with their emotions, rather than seeking to distract from them.

Suppressing the desire to broadcast

To paraphrase Stephen Covey, active listening is the difference between “listening to understand” and “listening to reply”. A difficult skill for any adult to master perhaps, but potentially even more so for children. This is the first generation to grow up inside a highly addictive digital world – where people are in constant ‘broadcast mode.’ Just think of the content creators and TikTok gurus with a constant flow of 30-second soundbites of advice, opinion and quick-fixes.

And yet active listening skills are essential for all of us (teachers, parents, students, employees, managers) to become more empathetic and more productive – so where should we start?

Active listening: 7 principles

Practising good active listening involves suppressing our ego and shifting the locus of communication to the other person – giving them permission to offload (usually on an emotive topic). In doing so we become aware and responsive towards their feelings – something psychologists refer to as “attunement.”

It can be helpful to break it down into the following principles:

- Paying attention – using non-verbal and verbal cues; such as turning your body and head, and maintaining good eye contact (exceptions being when the other person finds this threatening or culturally inappropriate).

- Encouraging – nodding, smiling (or frowning in empathy as appropriate) as well as short interjections.

- Eliciting – asking open-ended questions to draw more from the speaker. This can sometimes mean just waiting in silence, allowing the other person time to process their thoughts and emotions. ”What else?”

- Reflecting and Clarifying – making inferences and checking they are correct, helps to show the person that we care as well as helping us get on the same page. Mirroring some of their language can also help with attunement. “This situation is clearly leaving you drained, as you say – and it’s having an impact at home too – am I right?” Or “Help me understand…is it that…?” “It seems the crux of the issue is….”

- Validating – acknowledging the gravity of the situation and accepting the person’s emotional response. “It sounds like this past week has been very hard for you – that must be really tough” or “I’m so glad you spoke to me because this is really important.”

- Summarising – using all that we’ve learned from the speaker so far to paraphrase what they have said. “So you’re really missing Adam since he moved to France, he was your best friend and a good listener and it’s taken you longer than you thought to realise how important he was and now you feel really sad that he’s not around to talk to after school.”

- Guiding – giving advice (if there is any to be given) should always come at the end of the process and if possible be focused on inspiring the other person to investigate solutions. ”Some people find it helpful to try X or Y.” If it’s a work problem a colleague is raising you don’t always have to agree with them but you do need to convey to them that you’re taking what they’ve said on board.

Some things to avoid

Sometimes it’s also useful to understand what can derail active listening.

- Assuming you know what it feels like; before really giving the other person the opportunity to tell you. If a colleague is having anxiety adjusting to a step up, cutting straight in with “I remember when I joined the senior leadership team – it was a big leap but I just kept ploughing on and eventually things settled down” fails to acknowledge the immediacy of their feelings and can emphasise the distance between you.

- Interrupting; although sometimes useful, it takes a very skilled listener to know when and how to do this. Better to sit tight and wait.

- Shifting the emphasis back onto you; can be damaging even with the best of intentions. Take a family break-up, for example. An adult responding; “My Dad walked out on me too, when I was younger than you”, often means the young person will hear; “This happened to me. In fact it was worse for me, but I dealt with it and so should you.” In other scenarios our own feelings of insecurity creep out “at least you know what the problem is with your project – I don’t even know how to get started….” or “you’re going to do great – it took me years to learn how to get through OFSTED without being nervous.”

- Being fearful of silence; one of the most surprisingly difficult parts of active listening but some of the best introspection can come from letting it linger. It’s difficult to judge the best cadence admittedly.

Encouraging active listening skills in children

Like many social skills, active listening can be understood on different levels. While primary school PSHE lessons may focus more on basic behaviour, making eye contact, thinking about what has been said before you respond, not getting distracted etc. it’s only once children become older that they can more fully grasp the seven principles mentioned above.

There are two important points to consider before attempting to teach or develop these skills in others. Firstly, it’s really important that young people are able to understand the full value and purpose behind active listening and so want to engage with it. Secondly, we need to check-in with the other adults around them – are we modelling it often – and correctly?

There are many contexts in which learners can start to practice their skills, before they dive headfirst into more emotionally heavyweight conversations; in English and PSHE lessons and in smaller groups such as on student councils and during form time, for example. Active listening skills can also form an essential part of restorative justice systems where both parties listen to one another’s grievances. In all instances, pupils should be recognised and praised when they make an effort and/or do it well.

[We’ve pulled together a few ideas for active listening activities aimed at teenagers that you can download here.]

Helping children in distress

If a child is finding something difficult then teachers may well find themselves at the first point of call and sometimes can help right away. However, when a young person is in distress the situation changes. There may be safeguarding concerns, you may need to refer to your designated safeguarding lead or SMHL.

The role of ELSAs

One great way that schools can provide small group or one-to-one support to help children experiencing anxiety, bereavement, anger or other social/emotional needs is by using ELSAs (Emotional Literacy Support Assistants).

ELSAs, often teaching assistants, receive training in active listening (and basic counselling techniques) from educational psychologists and participate in regular supervision. It allows them to form personal connections with children they are working with who often need more time and space to process their emotions. Schools that have started ELSA programmes frequently report many positive benefits including improved attendance, positive feedback from teachers and parents and of course significant improvement in self-reported well-being from pupils themselves.

You can now train to be an ELSA as part of the recently launched Level 5 Specialist Teaching Assistant apprenticeship which is fully funded through the Government’s apprenticeship levy.

Sound draining? You’re probably doing it right.

Anyone can get started with active listening but it may not feel natural at first. Counsellors and EPs spend years honing their skills to be able to practice at a more nuanced level with more complex conversations.

Observe others who do this well in your school. It might be someone on your senior leadership team, a fellow teacher or a dinner lady. Some older children are surprisingly good at it. If you line manage others or interact with parents of vulnerable children, think about these interactions too.

The effort we put in pays dividends. Some level of active listening (however basic) is a valuable skill for us all. It can help us to function better in our family unit, as part of a more inclusive school, and in a more productive workplace.

Find out more: Courses

Explore the Level 5 Specialist Teaching Assistant apprenticeship with ELSA qualification

Find out how to become a better coach or mentor in a school environment in our Coaching and Mentoring in Education course.

Further active listening resources

Active Listening for Teens: Take a look at our ideas for PSHE activities here

Harvard Business Review: A great video about active listening in a line-management context: www.youtube.com/watch?v=aDMtx5ivKK0

Brené Brown on Empathy: A powerful video that neatly explains the difference between listening with empathy and listening with sympathy: youtube.com/watch?v=1Evwgu369Jw&vl=en-GB

Education Support: Jacob Morgan, author and Founder of Founder of FutureOfWorkUniversity.com introduces the BUILD acronym: jacobm.medium.com/5-ways-to-practice-active-listening-924b58746494